In India, five years ago, I worked in a school which was seeking to transform the lives of some of the poorest children in the country, by giving them a world-class education. The school contained slightly over 200 students – of whom I actually taught about 45. Whenever I caught the thrice-daily bus into the nearest town, I would see the same number of children, in a few minutes. The gap between what my school was providing – the school is now producing high-scoring students who are attending some of the best universities in India – and the life chances of these students never failed to depress me enormously. What could one school achieve when 300 million people in India are classified as rural poor?

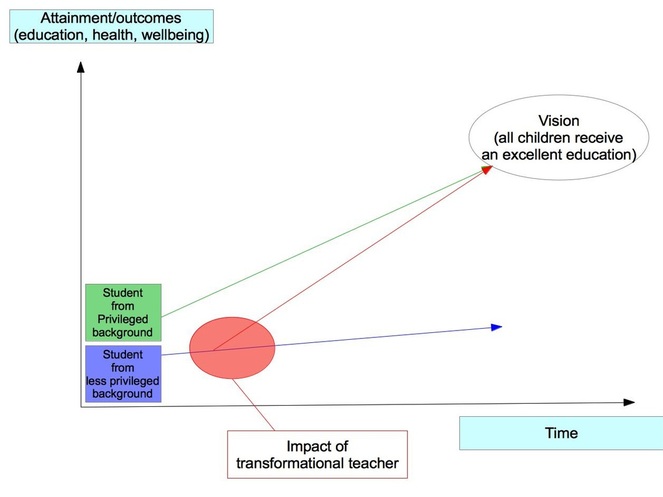

I finally got an answer which satisfied me from Steven Farrm, who I saw at InspirED India, a conference organised by Teach For India, last weekend. The rest of this post is a gloss on the case he made there – work based on his research into transformational teachers – those who change the life chances of those they teach.Firstly, Farr argues that education, and even a single teacher, can change a child’s future – the graph below shows this very simply – students from deprived backgrounds tend to head towards poorer life outcomes than those from more advantaged ones. The effect of the transformational teacher is to convert that path into one in which those deprived students’ life-paths are changed to attain the same result.

This graph pretty can be adapted for anywhere – one of Farr’s most compelling descriptions was that of Anam, a teacher in Pakistan: unable to prevent her girl students being taken out of school to marry at 13 or 14, she looked at what they needed to succeed having married – having identified skill in collaborating with other women as the key differentiator in happiness and fulfilment, she taught this to her students. In the UK, depending on where you stand, this might mean equal attainment at GCSE, attendance at university – an intense debate I shall shirk right now.

Farr argues that teachers who achieve this transformation tend to be distinctive in their:

– visions for their students’ futures

– prioritisation of students’ beliefs (in themselves)

– their backwards planning – from what they want students to achieve to how this will be achieved

– their conceptions of their role – they see themselves as ‘the person who’s going to get the students where they need to be’ – the famed idea that these teachers do ‘whatever it takes’.

The second key point in the argument, is that pursuing transformation learning in others, we become transformation leaders ourselves. He notes that to achieve all students gaining an excellent education, we need radically different systems and outcomes. In seeking to achieve the changes in children’s futures suggested above, we change too – in his words: ‘when we do right by our kids, we build the leadership in ourselves to change the world’. The changes we seek to inculcate in our students – and the methods we use to do so, we replicate as headteachers and leaders later on.

Finally, Farr looks at the consequences of this transformational teaching and leadership – what does it change? and gives three ways in which transformational teaching offers a route to educational equity:

2) The creation of ‘proof points’ – classrooms, schools, school districts proving that success need not be a result of social class, background or inheritance and that deprived children can equal and surpass their advantaged peers – which dismantles some of the ‘justifications’ for inequality.

3) The creation of leaders of the future who will take over the movement; in his words, “No movement for social justice has ever succeeded without leaders who have suffered that injustice”.

This third point which was totally new to me and offered a longer-term vision for educational equity. There are questions to be raised about it too. One we noted was the social exclusivity of some ‘Teach For’ programmes (the educational and financial barriers which can act to limit access to them to those who are benefitting from the status quo) – although equally I recognise that Teach For America, the most mature programme, has made increasing diversity of participation a key target for itself, and my cohort at Teach First was the first to include students who had been taught by Teach First teachers.

It seems appropriate to add a possible fourth point made to me by Anasuya Menon (Teach For India) subsequently in explaining why she is part of the organisation: the problems we are wrestling with are highly complicated and multi-faceted. Speaking of the Indian context, but offering an argument which I think remains true worldwide, she argued that by promoting the ‘leaders in all fields’ approach, whereby teachers enter a range of roles in society after their two year ‘fellowship’ as a teacher, leaders are placed in key positions across government, business and the third sector who understand the problems and wish to act to solve them. As such, ‘Teach For’ organisations are unusual in offering complex solutions to complex problems, rather than addressing isolated aspects.

Why is this so significant to me? These answers represent a holistic explanation why these things matter – and why the role in the classroom can be as powerful as the governmental roles to which we often look for solutions.

An essay which I read early on in my time in India came back to me in the words of many conversations – in Rahul’s, when he explained he’d rather be in schools, where he can make a difference, than in government. In discussing Alasdair Gray’s story Lanark, it quoted the following section: a delegate is sent to the council and the council leader tells him: ‘You suffer from the oldest delusion in politics… You think you can change the world by talking to a leader. [But] leaders are the effects, not the causes of changes.’ Later in the book the protagonist is told by his son ‘Of course you changed nothing. The world is only improved by people who do ordinary jobs and refused to be bullied. Nobody can persuade owners to share with makers when makers won’t shift for themselves.’

Perhaps you got this already. Perhaps you saw the broader significance of your daily work, beyond the lives of the children you teach. Although I’d been introduced to aspects of the arguments presented above beforehand, I didn’t. I hope it helps![Originally posted 2nd March, 2013]

I recognize that Teach For America, the most mature program-me, has made increasing diversity of participation a key target for itself, and best of luck tackling those big projects.