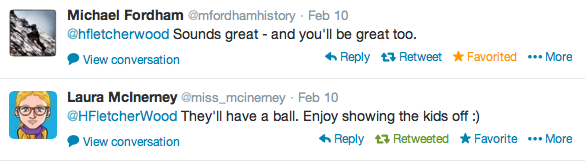

Are we a successful school? Let me start with the encouraging words of two teachers whose opinions I respect enormously and who have both visited the school this academic year. On hearing we were to be inspected, they wrote:

Are we an effective school? I have brilliant colleagues. I teach wonderful students. Between the two, some pretty amazing stuff happens. Moonlighting Ofsted inspectors at our Mocksted last summer showered us with praise. I’ve visited nine schools since we opened, with Ofsted grades ranging from ‘Requiring Improvement’ to ‘Outstanding.’ I’ve learned from all of them; none has shaken my pride in what we’re doing or led me to question our direction. Like all schools and teachers, there are areas of our practice which are strong, aspects we are prioritising improving, things set aside to improve upon in due course.

Given my limited contact with the team, I struggle to explain what happened. Perhaps readers should simply rely on the Ofsted report. Let me hedge, again, around the fact that I am writing this as an individual, and one who is clearly ill-qualified to offer much in the way of wisdom on this subject. It appears, however, that there were two big issues for the team:

1) An apparent gap in progress between students with Special Educational Needs and in receipt of Pupil Premium and others at the end of last year in English and Maths. (The data for the Autumn term this year suggests this gap has evaporated)

2) Our move from using Key Stage 3 National Curriculum levels for internal tracking purposes to using GCSE grades (from Year 7 on). To be fair to inspectors, we are probably the only school in the country who have done this; to be fair to us, that doesn’t mean we’ve done anything wrong.

Having seen this, it appears they had reached their conclusions. Much of what follows can, I think, only be understood in that light.

Failings in our teaching – verbal feedback

A series of examples of failings in our teaching were made by inspectors, of which three stand out to me:

a) In a mixed ability Year 7 lesson, there was a difference in student outcomes which demonstrated we were failing students with SEN. Given that students’ attainment on entry ranged from Level 2 to Level 6, a uniform student outcome would have been both an achievement, and a questionable one.

b) In another lesson, a student became stuck briefly with one task. The teacher identified his need, offered him individual support ensuring he was able to demonstrate understanding and complete the task successfully by the end of the lesson. This brief period in which he could not immediately demonstrate success meant that it could be graded (another graded lesson) no more than a ‘2.’ My colleague described the conversation thus:

Colleague: But he was able to do it by the end.

Inspector: But he struggled.

c) Students showed insufficient zest for learning – because they were not seen asking for extension work. How anyone could meet a cross-section of our students and believe this beggars belief, but I also wonder how this fits my lessons – ‘extension’ tasks are almost invariably built into the initial task and explanation, so if students are asking for ‘extension work’ they’ve often missed the point.

Failings in our teaching – written feedback

The areas for improvement for teaching and learning – the one thing I feel qualified to comment on – are the following:

- making sure that teaching caters more for students of different abilities

- making sure that all marking shows students how to improve the standard of their work

- increasing opportunities for students to write at greater length.

The example above on the difference in student outcomes and the student struggling in a lesson may be sufficient to suggest that our conception of teaching and differentiation, and that of the inspection team, are very different in how to cater for students with diverse needs.

Bad behaviour on a building site

- As a result of a clear and robust approach to managing behaviour, students are clear about what is expected of them and how they can play their part in promoting good behaviour.

- Students’ behaviour around the site is very good, especially in view of the limited space available as the site is being developed. Students act with care and consideration for each other and are excellent ambassadors for the school when visitors arrive.

A little context. This is the view from my classroom window. Six feet away, there is sustained drilling, sawing, builders working on the scaffolding. When I close the windows to shut out the noise, the heat rises to intolerable levels.

The devil’s in the data

On the brink of publishing this, I realise that I need to say something more about data. Our sole externally comparable data from our first year was the application of a National Curriculum level to end of year exams in core subjects (we developed other internal forms of tracking, on which more below). It was on the gaps this data appeared to show which the school was criticised.

I think we were naive – I certainly didn’t appreciate how much would ride on this (not that I knew much about it, not teaching a core subject). We had invested a good deal of time in trying to create new ways of assessing tracking progress. One of these, the thing we report upon to parents and students, is ‘progress numbers’ – which I believe are substantially better than any level or grade, because they reflect improvement, not absolute attainment – so a student may receive a high ‘progress number’ for low attainment which represents a significant jump for them; conversely, ‘good work’ may result in a low ‘progress number’ for a coasting student.

As Ofsted came increasingly into focus this year and we moved towards GCSEs, we applied a new form of internal tracking, based on GCSE grades. I question how well this applies to history lessons – but it appears to fit core subjects – of this system, inspectors note ‘it is too early to draw definite conclusions from this information.’ I question how useful and accurate any such system is, given the known inconsistencies in marking between different teachers. I wonder how easy it is to draw definite conclusions from any form of data in the second year of a school’s existence.

I don’t absolve schools from tracking students progress. I do reject the idea that such limited sources of data should be seen as more significant than what is happening in lessons. The inspectors took things the wrong way around I believe (a complaint which has been made by other schools recently) seeing problematic data as gospel and then seeking evidence which upheld this conclusion. It is this which makes the inspection report seem inconsistent: the praise for the school’s strengths sometimes seems to diverge from the criticisms and grades given.

Breaking bad news

To go back to the narrative of the inspection, we met just before six at the end of Day 2 – knowing that all had not gone as we might have wished, we opened the cava in advance of hearing the judgment.

Having taken photos to chronicle every stage of the growth of the school so far, this was the first moment at which I felt it would have been wrong to do so. Broken, shocked faces attended to our assistant head’s brief summary of the judgments. Achievement was a 3. Although 70% of lessons were ‘good’ or ‘outstanding,’ teaching and learning was a 3. The lack of ‘zest’ meant behaviour and safety was a 2. Unsurprisingly therefore, leadership and management was also a 3.

The Assistant Head handed over to one our governors, who recapped some key points: Ofsted exists, he noted, to provide information. Since we had not received a 4, they had not power to enforce change. The governors do not share their conclusions – they think we are an excellent school. Some changes will be needed in the way we present our data, but he undertook to seek to ensure as little changed as possible in the classrooms.

So how do I feel about the school’s inspection

It seems to me that inspectors arrived, checked the data, reached their conclusions and went out to find the evidence that suited these conclusions. My experience, described yesterday, of inconsistent lesson observations, was mirrored around the school. I don’t know what we deserve as a grade. On a personal level, I’m not particularly interested. But, I find the grade that we did get surprising, and the process by which we got it opaque, to say the least.

The inspection write up

Part I introduced the inspection, offered a metaphor I’ve found helpful in describing what happened, explained my rationale for writing about it and provided a disclaimer that this was just a personal blog.

Part II discusses my experience of inspection as a teacher and middle leader

Part IV raises five questions which inspection has left me with.

Part V looks at what happened after the Inspection.

The Ofsted report can be found here. The school’s response is here.

My colleague Will Lau has written a thorough account of his take on the inspection judgments.

For another source on the school, you could consider the school’s Parent View (one highlight is that, as of today, 97% of parents would recommend the school to another parent).

It may also be of interest to read the thoughts of some previous visitors to the school, Laura McInerney in the Guardian, Bagehot in the Economist and Roger Scruton in The Spectator.

*In a classic case of falling between stools, a maths lesson which, in response to this concern about extended writing, had been set aside to write-up an investigation as a way of incorporating literacy into the lesson, was deemed insufficiently mathematical by Ofsted inspectors.

Have you reported this behaviour to OFSTED?

The school put in a response to the draft report which I believe ran to 13,500 words.

The revelations in this post are astonishing and frightening. I’m reeling from the inappropriateness of inspectors asking students what level they are at on Bloom’s taxonomy, and actually rocking with laughter at the outrageous absurdity of the catch-22 you described in your footnote.

I’m appalled that a student’s temporary struggle is taken as a sign of incompetence rather than as evidence of learning. (Incidentally, on the Philosophy Foundation blog, Peter Worley has some interesting things to say about perplexity and confusion leading to learning – see http://philosophyfoundation.wordpress.com/2013/01/19/confusion-leading-to-learning/.)

The claim of ‘insufficient zest’ – measured so arbitrarily – and the incongruity between teaching quality observed in actual classrooms and the overall summative judgement of teaching and learning quality are further indications that all is not right with this process. It’s deeply disturbing to think that confirmation bias could lie at the heart of these adverse judgements and that the classroom observations themselves could be more or less perfunctory.

I hope this experience won’t have a lasting effect on morale within your school, which appears by all other accounts to be a wonderful and inspiring place to work and learn.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Reblogged this on Primary Blogging.

Another excellent blog. Restrained, but infused with passion.

Until this series of blogs I wasn’t aware of any of the background. I followed you on twitter, Harry, because of your excellent blog posts, but was never aware of where you taught, or the newness of your school. I did note that you were Ofsteded from your tweets, but didn’t realise the political/topical nature of the situation, with your school being a free school. The main thing that seems to emerge from this blog is the confusion promulgated by the inspection…but. also, the underlying confidence that the school has. After 2 years, I don’t see that the question ‘Are we a successful school?’, has any real meaning. I look forward to the rest of the series.

Thanks again CP. I’ve tried to detach my writing (hitherto) from my school – because I don’t subscribe to a doctrine that marks free schools out as particularly different from others!

I agree with you about the misguided nature of my own question too – all schools are works in progress, as far as I can see. The only question worth asking is ‘is the progress in the right direction and sufficiently rapid?’