History matters

I intend to cut the Gordian Knot limiting thinking about the history curriculum.

This sentence draws on historical knowledge, which is where the joy of learning begins, and the trouble starts. A reader might just recognise the expression, but to appreciate why I’ve chosen it, they might also wish to know that the knot was too tangled to be undone, that Alexander the Great decisively solved the problem and that he subsequently conquered the majority of the known world. In employing this metaphor when writing about London schools, Joe Kirby (from whom I stole the idea of this as a hook) was careful to clarify this. Without historical knowledge this statement risks meaninglessness.

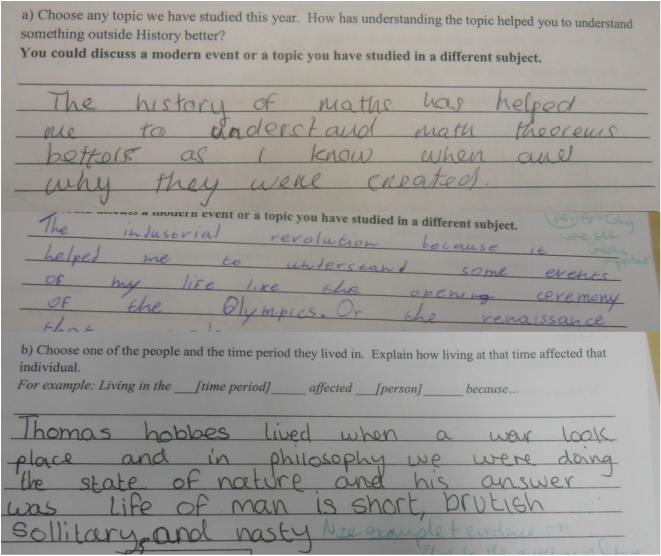

This is just one example; an overview of history is essential to understanding any single event, person or period; it also underpins other disciplines. It is impossible, for example, to appreciate the departure the Renaissance represented without knowledge of what had come before and what came after. As ED Hirsch and his disciples have argued, an understanding of literature, the arts, politics and citizenship relies on a historical and contextual understanding. Joe Kirby’s recent discussion of a scheme of work on Oliver Twist demonstrates the knowledge required about Dickens and Victorian London to respond to the book critically. The course I have taught this year on the history of maths suggests the same applies to mathematical developments.

Gaps in historical knowledge undermine mastery of other disciplines; Hirsch’s work has, in turn, helped guide Michael Gove’s approach to the new curriculum. Like many others, he is deeply worried about our historical ignorance.

Deep ignorance…

One teacher found her pupils confused over whether Iran and Iraq were the same country; whether Sydney was in California; and whether Henry VIII is the Queen’s son. Another teacher mentions here that 16 year olds couldn’t place their city on a map of Britain, list the four countries that make up the UK, tell the difference between England and Great Britain, or name the date of one significant historical event. Still another teacher and education blogger I know told me that her pupils thought Manchester was in Scotland, Wales was an island and the Romans came from Portugal.”

Superficial measures…

Rafts of these polls exist, first demonstrating students’ ignorance of history, then dissecting the causes and consequences. They are accompanied by quotations from historians or ministers, declaiming “There is nothing difficult about the concepts being discussed and no reason why a child of primary school age should not be able to understand” (David Starkey); lamenting the: “depressing evidence of the state of teaching knowledge in history” (Nick Gibb); or complaining this “denies children the opportunity to hear our island story” and promising “this trashing of our past has to stop” (Michael Gove). Yet these polls are distinctly self-serving; they give an inaccurate impression of curricular knowledge while obscuring the real constraints on the curriculum.

The methodology of these polls as a way to assess historical knowledge is often flawed. Michael Gove’s use of unpublished surveys has been highlighted, rightly. Even professionally-conducted polls are problematic: for example, when considering the results of a survey of 1,309 10-14 year-olds on their knowledge of D-Day, it’s worth remembering that most schools teach World War II in Year 9. Given they are unlikely to have been taught the topic, lack of knowledge on the part of three quarters of these students may seem less surprising.

The interpretations placed upon these polls compounds the problem. Derek Mathews’ excoriation of history teachers claimed that “This collapse in historical knowledge is a relatively new phenomenon. A recent survey by the BBC found that while 71% of over 65 year olds knew the significance of the battle of the Boyne only 18% of 16-24 year olds did so (p.1).” I doubt this proves anything about how much better history education was fifty years ago; it is more likely to prove that people keep learning once they leave school.

Not only do these polls often fail to carry the weight of argument attached to them, their prominence often has less to do with their content than their promoters’ purposes. My favourite non-educational blogger has long highlighted the use of surveys by commercial organisations as a cheap way to gain publicity, arguing:

They’re commissioned by organisations with a vested interest. They ask blatantly obvious questions. They come up with tempting yet not terribly convincing conclusions. Then some PR demon rushes out a press release stating the conclusion they knew they were going to publish anyway, which coincidentally happens to recommend one of the company’s products or services. And finally, every time, lazy journalists across the media treat the outcome as proper news and reproduce the press release word for word in an orgy of free publicity.”

Historical polls are no different: the BBC’s survey discovering ignorance of the Holocaust preceded their programming on the subject; one might guess UKTV Gold had similar aims and Michael Gove’s Premier Inn poll suggested historical ignorance “can be rectified by visiting all the fantastic landmarks and places of interest the UK has to offer.”

Finding questions answered wrongly, as any teacher knows, rarely takes long; it’s even quicker if you are looking for wrong answers in the first place. Inaccurate statements from individuals, like : “‘It’s a day when everyone remembers the dead who fought,’ said a 14-year-old girl at a north Devon secondary school,” of D-Day, make fairly good copy, but finding one such wrong answer in a sample of 1,309 is not entirely remarkable.

This particular survey tested knowledge of:

– Britain’s wartime prime minister

– America’s wartime president

– Germany’s wartime leader

– the location of D-Day

– the names of two of the landing beaches

– the Supreme Allied Commander’s name

We are not told the other questions, although there were presumably more and had they been met with entertaining errors, I’m sure we would have been. I’ve noted that three quarters of these students are unlikely to have studied D-Day in school (we are not told); this survey, of course, was in the run up to the anniversary of D-Day. Another survey, in the run up to the anniversary for Dunkirk, or Arnhem, or the dropping of the atom bomb, would undoubtedly have unearthed similar results. With such an approach, it’s not hard to find knowledge gaps; as my experience with hinge questions has taught me, student misconceptions are manifold.

Were I seeking to be score points, I might suggest the obvious solution. Premier Inn could take over part of the history curriculum. The BBC, having revealed half of adults were unaware of Auschwitz in 2004, were able to celebrate that this had rocketed to 94% a year later, implicitly linking this massive work of public education to their programming.

Underlying constraints…

Achievement was weaker in Key Stage 3 than in Key Stage 4 because of a number of factors: more non-specialist teaching; reductions in the time that schools allocated to history; and whole-school curriculum changes in Key Stage 3 in an increasing number of schools. (Ofsted, History For All, 2011, p.6)

Inspectors found so much good and outstanding teaching because the teachers knew their subject well. (Ibid., p.23)

Overall, achievement was weaker in Key Stage 3 than in Key Stage 4, and was weaker in Years 7 and 8 than in Year 9. This relative weakness was frequently associated with the deployment of non-specialist teachers. (Ibid., p.12)

It is entirely possible for students not to be taught history by a specialist history teacher at all during their school career. (Ibid., p.47)

In England, history is currently not compulsory for students beyond the age of 14 and those in schools offering a two-year Key Stage 3 course can stop studying history at the age of 13. England is unique in Europe in this respect. (Ibid., p.8)

In 14 of the 58 secondary schools visited between 2008 and 2010, whole-school curriculum changes were having a negative impact on teaching and learning in history at Key Stage 3. Some of these changes included introducing a two-year Key Stage 3 course, assimilating history into a humanities course or establishing a competency-based or skills-based course in Year 7 in place of history and other foundation subjects. Where these developments had taken place, curriculum time for teaching had been reduced and history was becoming marginalised. (Ibid., p.12)

Taken together, these have a huge impact on students’ historical understanding. Warren Valentine offered an example which may represent the nadir of history education: a school with a two-year Key Stage 3, which taught integrated Humanities on a carousel. Students spent less than 60 hours in their entire school career studying history, unless they chose it for GCSE (an unlikely decision after such an experience and a course for which they would almost certainly not be prepared).I’m not pretending that History is unique in its struggles. Ofsted’s History for All report referred to similar pressures on other Humanities subjects. Core subjects employ many non-specialist teachers too. Every Head of History I have ever known works hard to staff their department well, resist two-year Key Stage 3, ensure high numbers of students choose a history GCSE and so on. The point I wish to make is that we need to be realistic about the constraints upon how much history students can learn in school under the present conditions.We can make as many lists of unanswered questions as we like, but the time to provide those answers is sorely limited. We should also remember that not every single detail of every lesson will etch itself onto our students’ memories first time – we need time for repetition and consolidation. As the example of Gandalf’s discovery of America suggests, we also need to deal with students’ preconceptions, whether derived from Call of Duty, The Lord of the Rings, or Illuminati websites. So let’s allocate even more time for dealing with existing and emerging misconceptions.

With the best will in the world, and the best students in the world, in 60, or 180 hours, I am not going to convey the entire cultural heritage of Britain and the world to every student. I am going to struggle to ensure understanding and retention of Pitt, Peel and Palmerston; the Boyne, Boer War and Battle of Britain; Magna Carta, Michael Faraday and Mau Mau and everything else surveyed. Think about the D-Day survey… just memorising those individuals and understanding their roles is probably a lesson – and even then you’ll be caught out by the next question: Who was the most senior British commander? What were the Mulberry harbours? Where was the decoy operation?

Conclusion – when we plan a history curriculum we will need to…

1) An understanding of history is fundamental to human flourishing;

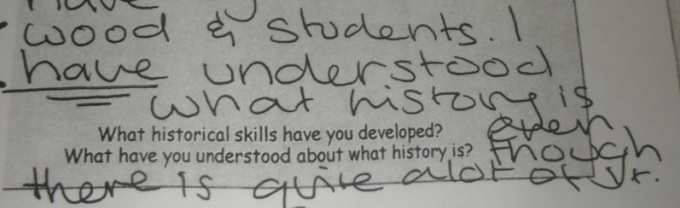

2) Even under optimal circumstances, our ability to ensure students’ knowledge and understanding of every significant event and individual we would wish them to know is severely constrained.I think I would be happy if history students complete their studies feeling a little like this:

(I have left the question of historical knowledge acquired in other subjects on the side for the time being).

[Originally posted 30th June, 2013]

Comments

I think you make an excellent defence of where history is, effectively using History for All which is a very balanced and reasonable snap shot of history in Britain. When Mike Maddison came into the Institute I spent some time studying History for All, with particular attention upon the list of secondary schools surveyed and, at a superficial level, it appeared to be quite a representative selection.

You are quite right about the issue of time. You therefore suggest that these discussions about knowledge versus skills or continued protests about knowledge are somewhat distracting. I agree with you entirely that much/most of what is slung in history’s direction is unfair. However, I did wonder as to whether you would agree with me that the ‘knowledge’ debate is still rather important, even if its framed in incorrect terms much of the time. Do we still see a lot of teachers focussing on skills alone or vice versa. I never meet any of these people, just here anecdotal evidence that schools are riddled with them!

I do very much look forward to your suggestions on how we can solve the Gordian Knot, having defended heads of department who I think receive a lot of stick for not defending our subject adequately. In the time constraints that we may well be presented with, and even if we did have our 2 subject specialist hours a week for three years I still think we’d be limited in how far we could meet idealistic expectations, how do we determine what knowledge we will deploy in our Key Stage Three curricula. You also hint in there about history dealt with in other subjects. Indeed, your history teaching seems to spread out at length other the other subjects*, how can we ensure that such cross-curricular excursions maximise students historical understanding as well as developing their knowledge of other subjects?

Thank you, as ever, for your thought-provoking response.

The knowledge debate has helped me to think more intelligently about the depth of understanding students require as a prerequisite to any form of explanation or analysis – and how we achieve this. As you say, the ideas are helpful, the way they are conveyed often less so.

I’m parking various issues for future blogs – one of which is cross-curricular learning . It doesn’t immediately affect how I would design the history curriculum, but as you say, it is something which we have exploited at school very heavily and I want to write about this in its own right.

You put the issue of knowledge in quite a helpful pithy way there. There is an excellent article in Teaching History by Woodcock about ‘the linguistic releasing the conceptual’, how students conceptual knowledge can be developed once we give them the vocabulary to express their thoughts as they come together. I often think of the knowledge in a similar way. It can be easy to forget the argument Counsell makes in favour of enquiry teaching: to really stretch and develop students’ thinking with the power of holding a story in one’s head.

Yes, when students finish their history study at 14 they do not have the intellectual maturity to develop the best understanding and wide ranging knowledge. However, despite the difficulties I don’t think History teachers have the memory of the facts as a clear goal in their teaching

…at KS3 anyway (I’m not commenting on your own teaching here!) and so we can’t be surprised when they don’t retain much of ‘the story’ they have been taught.

I think there’s another issue to be addressed. Have we as History teachers taken sufficient responsibility for constructing authentic curriculums as opposed to selling out to engaging ones? Many schools teach Hitlery rather than History, with the same topics taught in KS3, 4 and 5. This in turn reduces the frame of historical reference of History teachers joining the profession. What does a ‘best that has been thought and said’ History curriculum look like? I don’t think that the answer would be what we’ve got now. I look forward to your thoughts and at some point write something myself.

I think that the idea the real issue is that there seems to be fun (which is frivalous but keeps the children entertained) and challenging. The trick is to start with the challenging content and make it engaging – role play, acting, comic strips, etc as well as the traditional oral and written aspects. I taught a Year 3 class about different forms of Ancient Greek Government – age-appropriate but no attempts to dumb down with less difficult terminology. We then created a green-screen video and then wrote a booklet. The children loved it and their parents were incredibly impressed. If it says anything two of the children, on a trip to Stonehenge, were discussing whether the bronze age people could have lived in a democracy before coming to the conclusion they couldn’t because it was before the time of the Ancient Greeks. This conversation was not heard by me but a volunteer who was attending the trip!! It shows that when we teach challenging content it does have an impact. Also children love learning long or complicated words as it makes them feel grown up!!!