It should be dead easy to spot a new teacher, shouldn’t it…? The question hadn’t really occurred to me; had it done, I’d have assumed it should be obvious: a slight gap in subject knowledge perhaps, a struggle with a tricky group or a minor glitch in planning. In my previous post, discussing classrooms in three Uncommon Schools in New York City, I suggested they are aptly named: their classrooms offer both a distinct subjective experience and exceptional outcomes. Another feature which stood out was my struggle to identify new teachers. After watching parts of an apparently flawless lesson, I learned that this was the teacher’s first year with Teach for America. In two schools, I found myself asking to be guided towards the least and most-experienced as I tried to distinguish between them.

How can I explain my struggle to identify experience? Explanations could focus on my limited skill as an observer, or the flaws in lesson evaluation. I would posit a third cause however: it’s impressive, and unusual, to be in a school in which every student and teacher appears to be pulling hard in the same direction. It can’t happen by accident; often, it doesn’t even happen by design. I believe that Uncommon Schools’ leadership and school culture are instrumental in helping new teachers to rival their more experienced colleague: this post attempts to explain why.

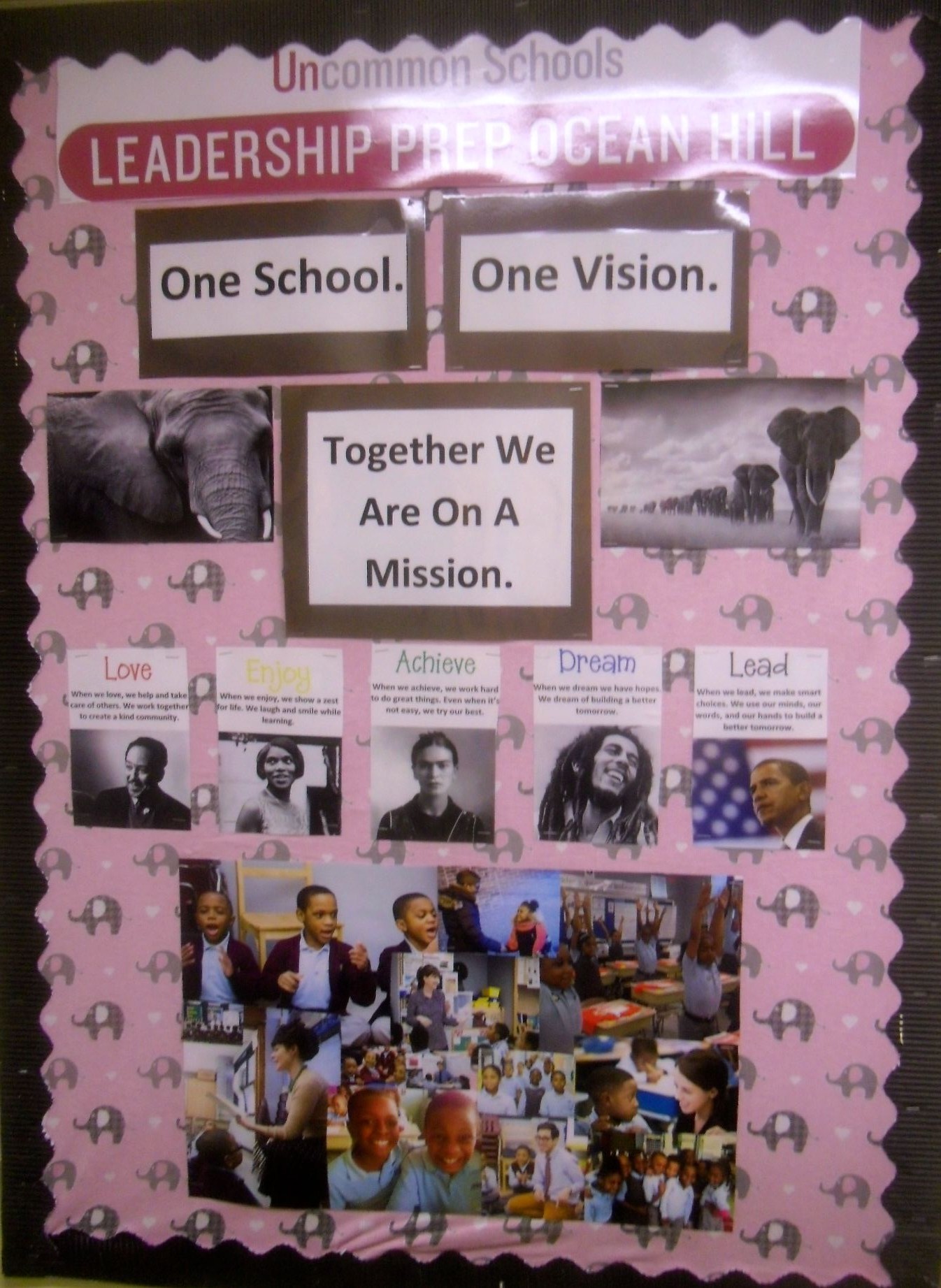

Uncommon Schools seem to have powerful cultures, which combine strong support with relentless focus on their mission. At Leadership Prep Ocean Hill Elementary (LPOH), Principal Nikki Bridges talked about the motivation their goal, closing the achievement gap and ‘changing history,’ gave them. Teachers were under pressure to fulfil their roles, but productively, reasonably and supportively so: Nikki noted that teachers like the “presence and attention” they receive, Sara Griffin, her colleague, described a “high degree of alignment and professional joy.” Teachers concurred, speaking highly of the feedback they receive and describing being part of a “happy staff.” Uncommon school leaders were sanguine about recruitment, given the competition for teachers and the mobility of New York residents: they have to create an environment in which teachers thrive and thus wish to stay.

“There’s no such thing as a great school without a great leader”

(an axiom from my tutor, David Cobb, which has stuck with me since my first day training)

Uncommon’s unusual bicephalous leadership structure appears to create the environment for great leadership. The principal focuses on teaching and learning, while the Director of Operations (DOO) “makes this possible,” in Nikki’s words, by managing strategy, systems and details. Sara Griffin, DOO at LPOH, mentioned that Uncommon are rare in having a school management career track (which presumably helps attract excellent candidates). They may lead on administration, but DOOs role as school leaders are clear: Sara had been a classroom teacher before taking up the role and in all three schools, DOOs were highly visible around the school actively ensuring the day was running smoothly. The role of the DOO appeared to be central to ensuring the school is well-administered and the principal can focus on their one, critical function.

Principals at Uncommon Schools have one critical role: improving teachers’ practice and students’ outcomes. Jesse Corburn at United Collegiate Charter School estimated he spends three quarters of his time on observing and coaching his teachers. Not only did all three principals at the schools I visited have time to talk to me, they appeared fairly relaxed: they had much to do, but a focus on the most important tasks. Nikki Bridges named her top foci as student culture, observations, planning for and giving feedback and being organised about deadlines and responsibilities (a list notable for what it omits as much as what it includes). Nor are principals alone in developing teachers: instructional leads fulfil a similar role in giving feedback and coaching.

How do principals develop their teachers?

Principals create a culture of improvement through a cycle of observation, feedback, practice, and implementation. Every teacher spoke highly of the quality and quantity of feedback and support and its effect on their teaching. For Britney, a first year Teach for America teacher, the three weeks of Uncommon summer school were a powerful grounding, primarily through role play. In her first weeks teaching, she received short daily observations from the principal and other leaders. Personal feedback (echoed by emailed notes) incorporated both ‘quick wins’ and long-term goals; during coaching meetings, teachers practise and role play to ensure they can put improvements into effect. Experienced staff likewise receive a weekly, unscheduled observation, followed by a feedback and coaching meeting. This may sound intense, but teachers have ‘bought in:’ Nikki argued the transparency of the process left staff in control; the teachers I discussed this with seemed hungry for feedback to help them develop. I was unsure where this left more experienced teachers: Scott Schuster at Kings Collegiate Charter School called Teach Like a Champion “more of a playbook” than a programme from which teachers graduate, but exactly how this works for more experienced staff remained a little unclear to me.

Doing amazing things for students is one thing: doing it in a way which teachers can sustain is a critical next step if great school practices are to be widely applicable. All three principals had thought carefully about this and were working on concrete measures to achieve this. Nikki Bridges talked about her colleagues’ sense of mission and the way feedback makes them feel appreciated, supported and helps them to grow. She also described the need to prioritise: not everything can be done to 100%, so she picked her top five things to do brilliantly and accepted a degree of give on others. Jesse Corburn mentioned UCCS was considering shortening the day and his wish to stabilise schedules so teachers keep and specialise in particular courses. Scott Schuster and Christie Chow discussed their attempts to reduce the stress on teachers by ensuring everything was ‘planned ahead’ rather than ‘fire-fighting,’ ensuring there were no alarms or surprises and possible problems in behaviour did not continue through the day. They also mentioned using a chunk of budget to keep staff happy – by feeding them, for example. Britney at LPOH also mentioned the school’s consistency as a boon. While retaining teachers remains a challenge and life in charter schools may never be say, I felt this move to sustainability was authentic and extremely credible.

I wonder whether British schools could examine the Director of Operations role to free headteachers to focus on teaching. Uncommon also appear to offer an example of the creation of an ethos of care, loyalty and hard work among their teachers (and students). Finally, the power of feedback shone through the schools: GFS will be following ARK in introducing Uncommon’s leverage observations next year as we try to capitalise on this.

Other reading

My first post focused on Uncommon classrooms. My next will look at professional development.

On charter schools

When I wrote about Ofsted inspecting my school, I emphasised my focus on inspections, not free school policy. Likewise, I’m not trying to discuss the arguments for or against charters, but explain the practices I saw at one chain.

With thanks to…

Doug Lemov for the chance to visit and Jen Kim who organised everything brilliantly. Nikki Bridges and Sara Griffin at Ocean Hill, Scott Schuster and Christie Chow at KCCS and Jesse Corburn and Liv Angiolillo at UCCS and the teachers who spoke to me.