Lollipop sticks are so simple: small cards, with every student’s name written upon them, used to nominate respondents.

What makes me believe they’re an invaluable teaching tool?

And why are they so contentious?

I’d swear by lollipop sticks and hate being without them, but having used them for years I’ve never written about them. They have been condemned as a faddish excrescence of AfL by David Didau, Joe Kirby and Tom Bennett, whose 1200 words critique I came across recently. Much as I respect all three, I think this misunderstands their power. A post explaining how I use them and why I think it matters formed itself in a colleague’s lesson recently – this is it.

How do lollipop sticks work in discussion?

(An idealised case):

1) Students prepare an answer to an open question. They write ideas on mini-whiteboards and may talk to partners, preparing an answer to a stimulus or question – giving them time to think through what they will say. I use this time to circulate and look at what students are writing, offering hints or challenges as appropriate. For example: Would you accept an OBE? Why might someone refuse one?

2) Questions, directed using lollipop sticks. I pose a question, pause, and choose a student at random. (Or if I’ve asked a ‘polarising’ question, like the example above, I may ask students to use traffic light cards so I can switch between argument and counter-argument).

3) Follow-up questions. I push almost every student with a follow-up question, depending on what they’ve said. I may ask for:

- elaboration (But what would the implications have been for the barons?)

- evidence (Can you give me an example of a benefit Britain brought to India?)

- reformulation (1) (Try again, giving the point first, then the supporting evidence).

- reformulation (2) (That evidence doesn’t prove the case – what else would?)

- responses to contradictory information (Why might parliament have opposed this?)

- links (Which other monarch found himself in this situation? What did he do?)

If the initial nominee struggles (given sufficient time and support), I may bounce the question to another peer (using lollipop sticks again) or take hands up if it’s very tricky, often returning to the original student.

4) Questions bounced to other students. Again, using lollipop sticks to nominate:

- Do you agree with what Sami said?

- Why might someone disagree?

- Are you satisfied with Jay’s response?

(Or we may move on to a fresh point).

5) Increasingly challenging questions. As we proceed, I adapt my questions to seek missed ideas, syntheses or increasingly complicated responses – still choosing at random.

6) Time for hands up. Near the discussion’s end, or if we’re reaching the extent of students’ understanding, I’ll ask for hands-up if students have original points.

A couple of tweaks:

a) Recycling cards. I may replace the sticks already used midway through the discussion – I’ll aim to hear from everybody at least once each lesson (so it’s important to use all of them), but students shouldn’t be content to give up after one contribution.

b) Wildcards. Each class set has three ‘wildcards:’ I may nominate someone from whom I’ve not heard, or I’ve been known to pencil in the name of a coasting student, doubling their participation for a month to add a little pressure.

Why do I think lollipop sticks matter?

They are democratising… They signal that every student in the class has an equal part to play.

They are democratising… They allocate time fairly: confident, loud, shy or bored, everyone has roughly the same opportunity to participate.

They help me balance access and challenge… Asking a question to which every student can respond while inviting high level responses is tricky – but if I can’t do it, some students’ time is being wasted. I don’t always succeed, but knowing that aim (and responsibility) helps me phrase my questions carefully.

They help discourage passengers… There is no magic bullet to ensure all students are thinking all the time, but knowing you may be called upon at any time (alongside techniques like ‘100%‘) helps. This seems particularly effective when asking students to prepare something as a group but noting that any one of them may be asked to feed back.

They raise my (and my students’ expectations)… I force myself to expect everyone to be able to answer constructively, thoughtfully and with evidence at any time. If I don’t provide scaffolding to help every student do so, I’ve let them down (if I must, I can do this individually after the discussion).

They can be finessed… This is no blunt instrument. Wildcards, for example, have had a significant impact as students feel and respond to the increased pressure. No doubt there are more tweaks to suggest.

What about the criticisms?

“Stop picking on people” – why shouldn’t students choose when they participate?

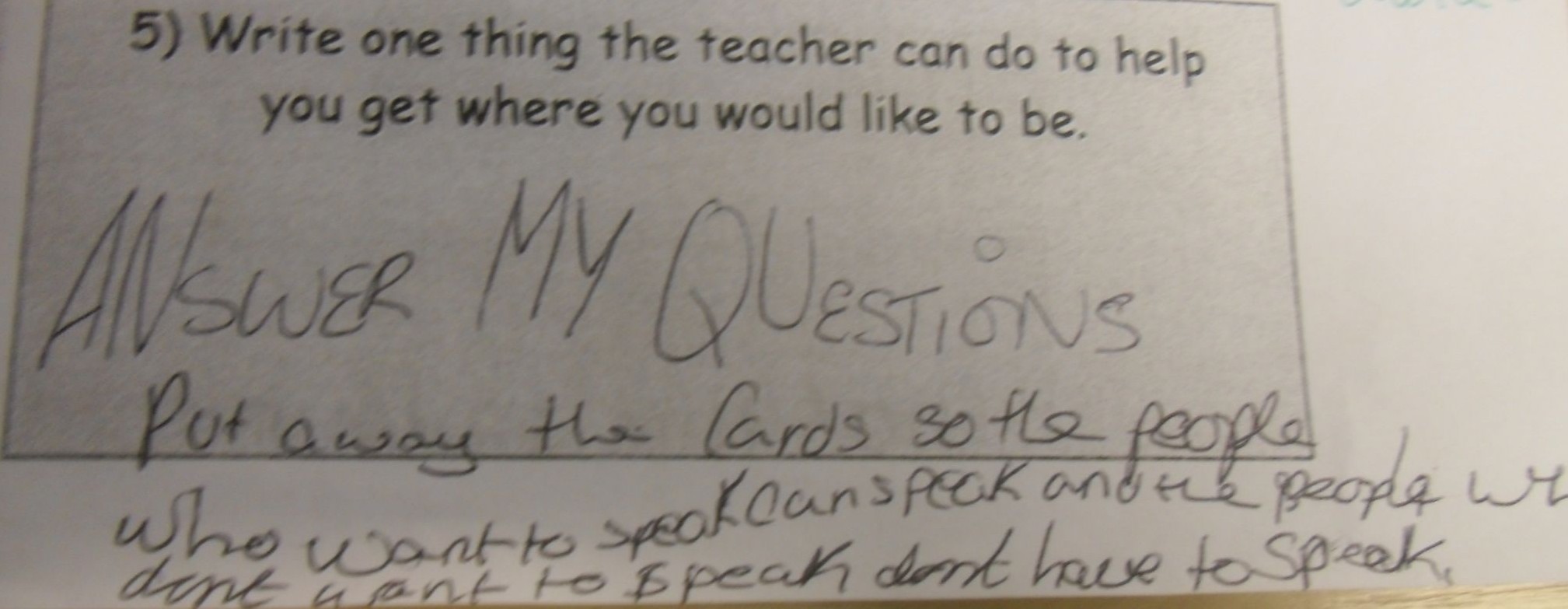

Student reflection sheets invariably include a handful of complaints thus:

As Dylan Wiliam notes, removing choice over participation radically changes the classroom contract. It’s universally unpopular: students who consider themselves weak don’t want this publicised; those who consider themselves smart are frustrated they can no longer dominate discussions and that time is being wasted on students who don’t know the answers.

Without lollipop sticks (or something similar), only a few students will consistently participate. Of the others, some will be listening; some will have great ideas but keep quiet, not realising; some will tune out. Everyone can offer something to discussions, but a little force is needed to demonstrate this. Ensuring all students are listening and responding sends a critical message that everyone should be participating in learning.

What about differentiation?

Many would argue that lollipop sticks need not be used to enforce participation. David Didau has written: “I’m not a fan of randomisers; the power to select who answers our questions should be treasured.”

Perhaps my ‘one question fits all’ approach is a function of teaching history. There is a single GCSE paper; most schools teach history in mixed ability classes; most enquiry questions would make good PhD theses (consider our current Year 8 topic: Why can’t we agree about the British Empire?) Asking different students different questions undermines this – all students face the same exam. And stuff the exam, all questions should be sufficiently clear and challenging that everyone benefits. I can then differentiate in follow-up questions, as I’ve described above.

Selecting students for our ‘targeted’ questions can, I believe, embed low expectations: I’ll ask X that, because he’ll get it right; I’ll save the hard question for Y. ‘Weak’ students never cease to surprise me with brilliant answers to hard questions, because they get the chance to answer. Equally, asking ‘simpler’ questions to ‘smarter’ students offers the chance to hear good answers modelled or, on occasion, highlights surprising gaps in their knowledge.

But what if some students don’t understand the question?

Why would a teacher ask a question they do not expect students to understand?

But they’re a fad.

Like any Assessment for Learning tool, yes – if misunderstood or misused.

It takes time to make them.

About half an hour at the beginning of the year.

In conclusion

I don’t claim to have perfected questioning and I usually try to avoid explicitly evangelising. I do think lollipop sticks matter, and I believe we should all be using them.

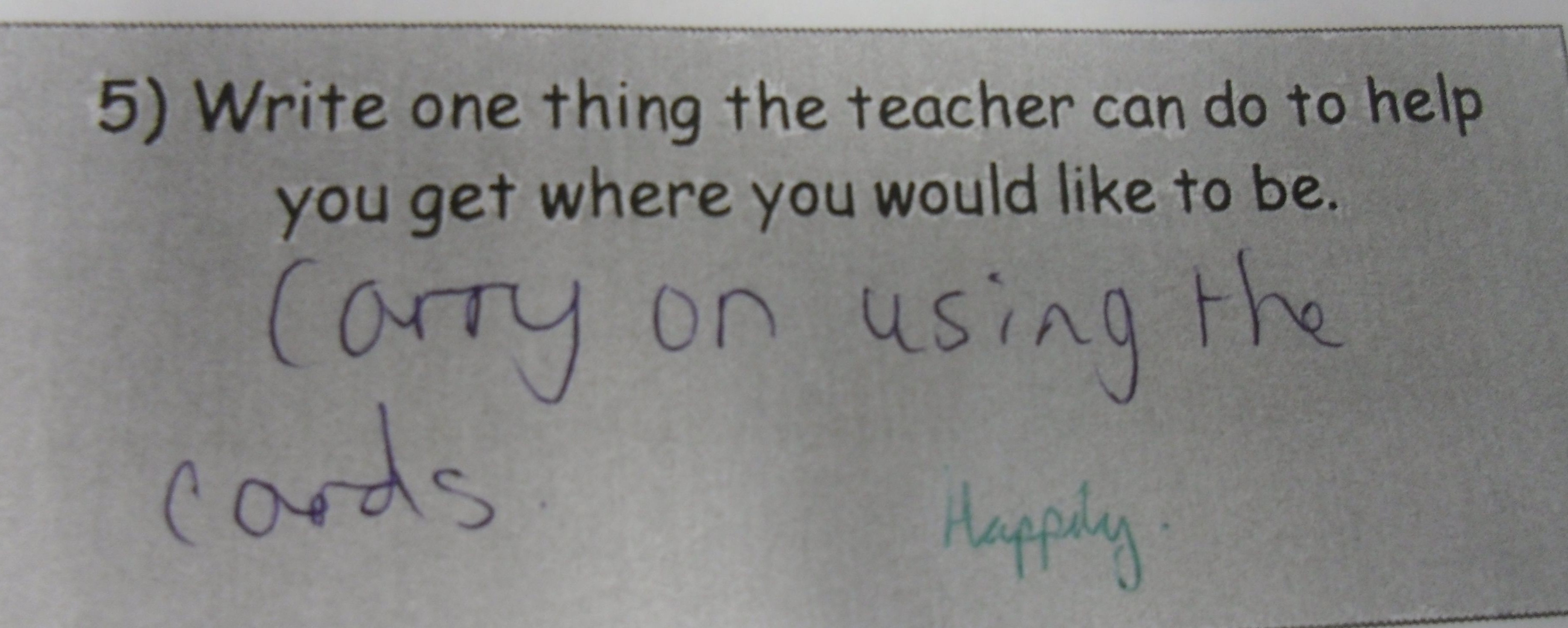

Did I mention – students eventually come around to it:

* I don’t even like the term ‘lollipop sticks.’ Mine are little cards.

I found this really interesting as I get sucked into these discussions even though I have a pretty “if you want” attitude to the strategy.

I don’t have a problem with lollipop sticks, and can see they might be useful. I haven’t used them (I did once create elaborate randomised powerpoints for each of my classes that did the same thing, however), but I don’t think it’s a terrible strategy.

However, I fail to see them as ‘invaluable’.

The reason is I just can’t see any significant advantage that couldn’t be equally applied by just choosing the pupil to answer yourself. In the case of your advantages, I think that’s because you’ve thought about ensuring those advantages, rather than the strategy.

I’m don’t think lolly sticks will help democratise if the pupils don’t feel they have a role to play already – and if they don’t feel they have a role to play this needs addressing via expectations. I’m not sure lolly sticks are helpful in raising expectations of those who don’t think they have a role to play – certainly not to a significant extent.

I think the “balance and challenge” part is a challenge anyway, but I wonder if one wants all students to be able to answer every question. Isn’t the point to ask a great question that illustrates knowledge and understanding, and the answer help the teacher to establish whether the pupils know and understand the subject of the question? Some pupils won’t – this isn’t a bad thing. One might even already know some pupils won’t but be expressing what you are expecting them to know by the end of the lesson or beyond. I’m not sure why one needs lolly sticks to have to think carefully about access to the questions. Indeed, I agree that planning questions is one of the best planning strategies, but I am not clear on why lolly sticks helps this.

I think all pupils should know they can be called on all the time in any lesson – and expected to answer even when they don’t know. I’m not sure who coined the “I don’t want to know what you know, I want to know what you think?” response to a pupil saying “I don’t know” but that should be a stock response. Again, why do we need lolly sticks. If they weren’t there, but you ensured pupils answer questions in every lesson do you think some pupils would stop thinking about questions because they weren’t there?

I’m also not sure about the “allocating time fairly” part. Surely the point is not to ensure equal time speaking, but to ensure all pupils are learning and able to access the learning – this does not necessarily imply all pupils get the same time, but that pupils get appropriate time from adults.

The only thing I can think of that might help is that the pupil’s explicitly know they have an equal chance of being chosen – rather than when you choose yourself – and in some way this might theoretically ensure that some don’t opt out.

I agree about targeted questions having the potential to embed low expectations. But targeted questions should be based on answers to previous questions, building on assessments from previous lessons (including questions) and we should be challenging ourselves to think hard about the questions we’re asking to whom. I find it strange to suggest that targeted questions are worse than questions asked at random. Again, I think one ensures that targeted questions don’t embed underachievement and low expectations by having thought carefully about questions rather than the strategy.

I do think there’s a separate point there that blunt “differentiation” itself encourages low expectations – particularly when planned for at the outset – one I have a lot of time for.

If it’s an advantage to choose by chance, rather than use one’s professionalism, great, use them. If teacher’s professional judgement is superior, don’t. I would contend the latter is more often better.

As I said, I don’t have a big objection to them, but I do think they’re too blunt.

Lots of interesting points here – for which thank you. Simply put, my own experience is that I struggle to choose students in a way which seems fair and demonstrates high expectations without them. I find myself falling prey to a feeling that: X won’t know this, I’ll skip them and ask Y who looks like they’re not concentrating or Z who will make the desired point and enable us to move on.

I agree that expectations should be far more broadly conceived than one strategy – but I think they prove useful as an early measure with a new class while all the other necessary strategies are brought into play.

I’m trying to move away from using verbal questions to find out what students think/know. If I want to do this, a hinge question or RAG marking is far more efficient. Verbal questioning is, in my view, more useful as a way to model thinking and for students to articulate ideas (enabling them to write them subsequently). I may discover students aren’t able to express what I’d hoped, in which case there may be a need for more explanation on my part, or thinking time/preparation on theirs. But the main aim is to ensure everyone here’s good ideas modelled. So I’d like to know everyone can do this.

Tom Bennett suggests that anyone worried about the tendency to question unfairly without lollipop sticks should see a careers counsellor – perhaps he’s right. Likewise, you suggest professional judgment should be more powerful than randomisation – perhaps I’m just a little short on the former! I’ll just retreat to that refuge that: ‘it works for me’ for the reasons I’ve given above.

I certainly didn’t mean to be offensive and don’t think that about you at all, as I hope you know.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

I was going for self-deprecating, not offended!

Reblogged this on Primary Blogging.

Tom’s point below is ridiculous:

“But what if the teacher is unconsciously biased towards certain children?

Then that teacher needs to think more closely about how he or she asks questions. If you seriously need lolly sticks to avoid picking children based on preference/ gender/ ethnicity/ agreeability etc then you don’t need lolly sticks, you need a sabbatical and a career adviser. I’m pretty confident that if you’re aware of the problem the. You can deal with it pretty sharp.”

The whole point is that it reduces cognitive load on the teacher. The teacher spends less time worrying about who to pick and in turn can spend more time formulating the scaffolding/further prompts as necessary.

I never used them before this year, but I would recommend that every teacher tries them if only to see the effect. In my classes, I find it works nicely with no opt out. You can also control the pace of questioning better. When used successfully, you can hear from every child in the class without having to think (and waste mental capacity) trying to remember who you haven’t asked.

Lastly, it avoids pupil complaints about being picked on/never chosen. Sticks are picked at random, how can it possibly be fixed? Well there are 3 ways, but there’s no need to go into that here!

Without intending to be rude to anyone at all, I find the whole discussion just a little ridiculous. When I say ridiculous, I mean that for teachers to be concerning themselves about such issues as lolly sticks holds the profession up to ridicule.

I can understand that as a profession, with little people’s minds and futures in our hands we have to be careful about the way we go about our jobs but to focus on the minutiae of daily practise is for me a little strange.

I use lolly sticks. I use them because my students are familiar with their use. My students are actively involved in choosing who will answer next and lolly sticks allow the lesson to proceed smoothly.

I believe when one starts to talk about lolly sticks in relation to cognitive load theory I feel the plot has been lost. When one starts to talk about lolly sticks in terms of high expectations I feel that the plot has been lost. When one speaks of lolly sticks and democtratisation I believe the plot has been lost.

I would like to coin the phrase “Edstremist” if it has not already been done, or the extremist educator. The “Edstremist” is one who has seems to exhibit many of the characteristics of other types of “ists”…..

-They are convinced that they are correct

-They are convinced that them being correct gives them the moral right to trample over other peoples beliefs

-They are paranoid, finding evidence everywhere and in everything that the “powers that be are against them” and their beliefs

-They justify what they do on the basis of ancient writings and often outdated morals, ethics and behaviours

-They try to indoctrinate other young educators with stories of evil Ofsted inspectors who will try to turn you from your beliefs

-They will gather vulnerable disciples by highlighting all of the things in modern education that cause suffering to educators and go against their particular doctrine

-They are more often interested in the adulation, attention and recognition that comes with conversion to their doctrine than with the efficacy of their doctrine (but anyway they are always right so hey…)

-Everyone who disagrees with their doctrine has a poor argument, they must have because hey……”they are always right>

-They are finding that with the new 21st century skills they has (which dont actually exist) they are able to reach a “new” target market of budding edstremists

-They see themselves as intellectuals who have developed expertise in every subject known to man and dismiss other intellectuals who really are experts in the blink of an eye

Why do I say this….because I feel that although the most radical edstremists are on the traditionalist side of things, there are also edstremists on the progressive side of things. (don’t like this categorisation but it seems popular).

Chatting about lolly sticks at break in the staffroom is one thing, but looking for evidence of efficacy in CLT is for me taking things a little too far.

To your former argument – that we shouldn’t be reflecting on the teaching strategies we use – I can only say that I couldn’t disagree more strongly. We have a very limited amount of time available to us and a huge range of things to achieve in that time. Carefully evaluating the smallest choices we make and choosing better next time is central to ensuring we use that time well.

To your latter point – that there are a group of ‘edstremists’ out there arrogantly trampling over the beliefs of others – I don’t know how many of my posts you’ve read, but I struggle to see any one of your list which can fairly be applied to me. I’ve changed my own views significantly over the last year and a half, and for that reason, among many others, try to avoid prescribing what others should do. For similar reasons, most of my points spend a good deal of time considering the weaknesses of my approaches.

To describe Harry as an edstremist is comical. Have you read his other (always reflective) posts?

There are many points I could make about this discussion—as you might imagine, I agree with what Harry has said, and find some of the responses baffling—but I will content myself with one, and that is to do with whether we should examine the minutiae of our practice. From my examination of research on expertise the answer is a resounding yes. In the health professions, tiny little details of practice matter. If a nurse applies a bandage in the wrong way, it moves out of position hours later and Atul Gawande, in his first article for the New Yorker in 1998 (“No mistake”) talked about the extraordinary economy of movement of surgeons at Toronto’s Shouldice Hospital (who do nothing but hernia repairs). In both “Teach like a champion” and “Practice perfect” Doug Lemov shows how well-ractised routines can create additional time for learning. In lesson study in Japan (but not, sadly, in the way it has been implemented in the UK) teachers spend literally hours wondering whether it is better to teach the area of the triangle before or after the area of a parallelogram (the answer is after, in case you’re interested).The details of what gets practiced will vary from teacher to teacher, but the idea that one should constantly be seeking to improve one’s practice seems to me to be an essential element of being a professional.

I completely agree with Harry and Dylan’s explanations as to why we need to be thinking about how we address our questioning, though I have some worries about the lollisticks which I’ll suggest in a moment.

One of my school’s biggest focuses this year has not been foisting a particular ‘gimmick’ on us, but having a good understanding of our own practice and be able to justify to ourselves why we do the things we do, i.e. our balance of open & close questions, or the ratio of pupil talk to teacher talk. In this spirit, I decided to print off a class register for one of my year eight classes and over the course of a fortnight (three lesson), document how many questions I put to the class. Beyond hands-up questioning (which, Harry, you rightfully suggest there is a time & a place for) it emerged that I did not select five students for questioning at all, and there was a slight skew towards asking the more difficult questions to the top.

My rectification for this was to keep the register and to tick off each student as I spoke to them, with the goal of speaking to all. This certainly helped ensure that the range of students was included, but I now accept that this is not necessarily a safeguard against preventing previously low-attaining students from answering my higher-order questions and think that perhaps I need to look again at a version of the lollisticks.

My worry though, is that students will come to expect lollisticks to be used every time. Has this been your experience Harry? I do want to retain the right to pick on any student to answer a question, as there are times when I think our professional judgement can and should trump a completely random selection of students – we may deliberately want to employ an alternative strategy. What is the way around this?

An interesting account. While I personally favour lollipop sticks, I think anything which makes us conscious of (and helps us amend) who we question and how we do it is good news – so your register and ticks are likely highly effective.

I think students come to understand the rationale for using lolly sticks, but very few of them really like them – most would far rather choose when to participate (and some would rather switch off). I’d be surprised (and a little affronted) for a student to turn around and say ‘why are you picking without the sticks?’ much as I would were I to hear ‘why are you using sticks?’ So I wouldn’t expect what you describe to be a problem. Ultimately, as you say, we are the professionals choosing – and I’d give equally short shrift to either of these questions!