Reinventing the wheel – a mistake?

Of the many criticisms I’ve received as a teacher, one I’ve failed to outgrow is ‘reinventing the wheel.’ In my training year, I remember my professional mentor complaining that new teachers, including me, waste time recreating or modifying existing resources. Last November, five years later, Kris Boulton and Nick Dennis were still taking me to task for advocating something similar for teachers seeking to incorporate new strategies in their classrooms. While it’s undoubtedly impractical and undesirable for new teachers to begin planning as though from a blank slate, I can think of fewer than half a dozen lessons I’ve borrowed without any modification at all; to meet my students’ needs, each idea and each lesson needs some degree of modification. The same holds true for new strategies: each one needs to be fitted in amongst all the existing practices of my teaching – and, in the process, made my own. So, while I think the criticism is well-founded, I have neither the desire nor the ability to stop myself in repeating it. All this is by way of introducing a recent recurrence of this tendency, this time in my marking.

I’ve never been the best of markers. At my former school, I found the expectation that every page should be marked every fortnight so impractical that I did not attempt to follow it. While I marked Key Stage 4 and 5 groups’ work regularly, usually weekly, my attempts to emulate my colleagues and do the same for Key Stage 3 classes were rapidly dashed on a treacherous reef of impracticality and undesirability: my need to plan my lessons, to preserve my own wellbeing – and the poor quality of much of the written work (the self-perpetuating vicious cycle of this last point is not lost on me).

Unfortunately, marking regularly is not one of the deficiencies in my teaching which I’ve addressed consistently. As my lessons have improved, I have interested my students more in the subject, promoted better understanding on their part – and thus found work more and more interesting, both for the ideas it contains and the growth it demonstrates. I’ve also learned to mark more efficiently: discovering ‘closing the gap’ marking hastened the process and showed me how beneficial targeted feedback could be. However, while I’ve marked more and better, I’ve never sought to offer weekly feedback on classwork for all my classes. I’ve implicitly relied on a heuristic the professional mentor I referred to above offered; as a teacher, he stated, your priorities were: 1) planning, 2) marking, 3) everything else. I’ve always planned carefully, which takes a lot of time… so marking has gone by the wayside.

A few months back, Joe Kirby and Katie Ashford offered a proposal which seemed characteristically bold, if not breathtakingly counter-intuitive, asking ‘What if you marked every book, every lesson?‘ Their approach had a seductive appeal similar to that which led me to introduce mini-whiteboards, hinge questions and coloured cards: they all offer ways to make transparent my students’ understanding on a minute-by-minute and day-by-day basis, instead of waiting for a half-termly assessment, by when it’s too late. A chance to reinvent the wheel! Since a new scheme of work at the start of this term, therefore, I’ve marked every student’s work, every lesson, for the hundred students of my four Year 8 classes.

Designing the wheel: How does the marking work?

Summary task: At the end of every lesson students wrote brief answers to a question which encapsulated the lesson’s key idea. It was often the lesson question itself, sometimes slightly rephrased; on average, students were writing for around five minutes.

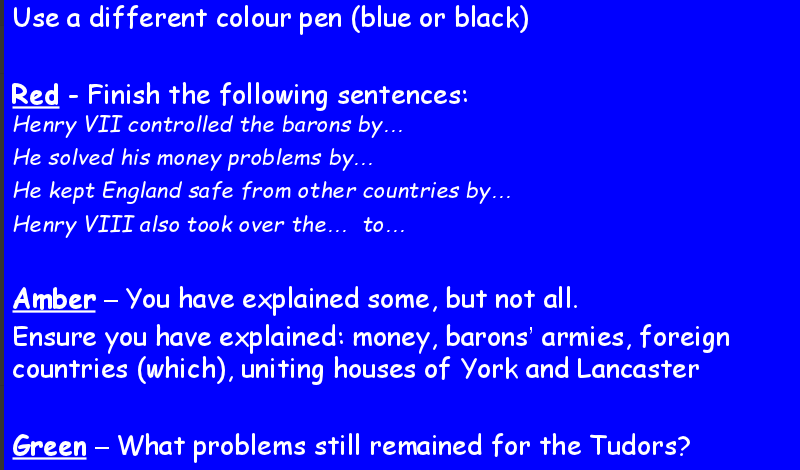

Marking: I collected their sheets and marked with coloured stickers:

Red – the answer is incorrect or incomplete;

Amber – the answer is correct, but lacks detail or overlooks nuances;

Green – the answer demonstrates a full understanding of the question & includes all key details.

I also marked literacy errors, and made occasional comments/specific pointers.

So the marking looks like this:

Improvement/DIRT time: Next lesson, after a hook, all students revisited their work for some DIRT time (which our school has christened, in homage to our – original – colleagues in the maths department, SCWEAC time: Scholarly Contemplation With Extension And Consolidation). Each colour directed students to a different task: in general, red tasks offered sentence-starters or broke the initial question into sub-questions; amber gave students prompts to check the inclusion of a number of details in their work while green gave students a new angle to take or question to consider. Since students retained the resources from previous lessons, they could refer to these to help them – I also explained common errors and occasionally retaught aspects of lesson with which a large number of students had struggled.

Checking: While students were doing this, I circulated very rapidly, checking students’ successful correction and improvement. The literacy marking and comments on the first marking were in green; I did this second marking in red, either ticking or writing further prompts or corrections or giving individual support as appropriate. At a push, I can get around every student in the class in five minutes and respond accordingly.

Record: I also noted students red, amber or green ‘marks’ in a spreadsheet.

Faster journeys? What is the effect of the marking?

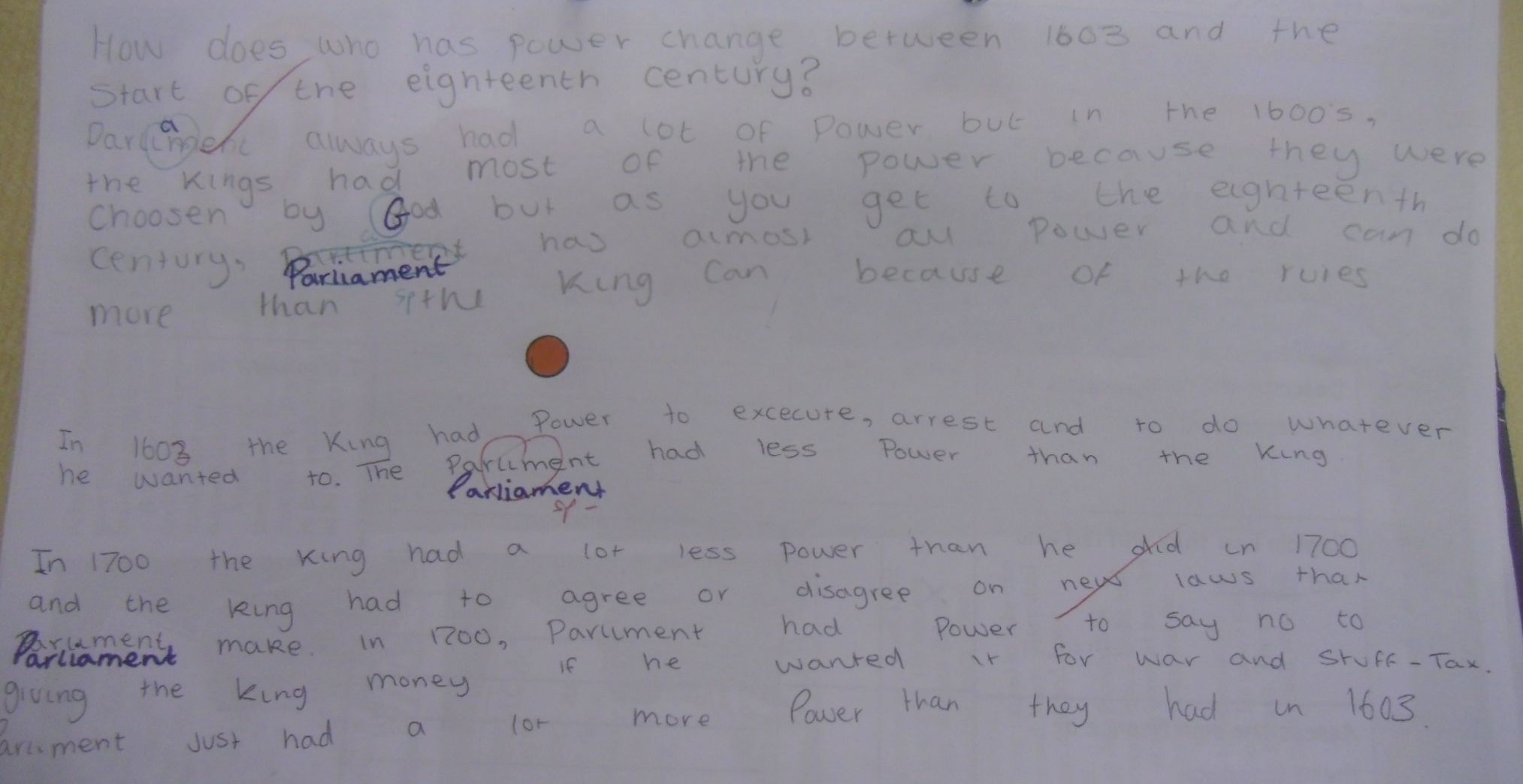

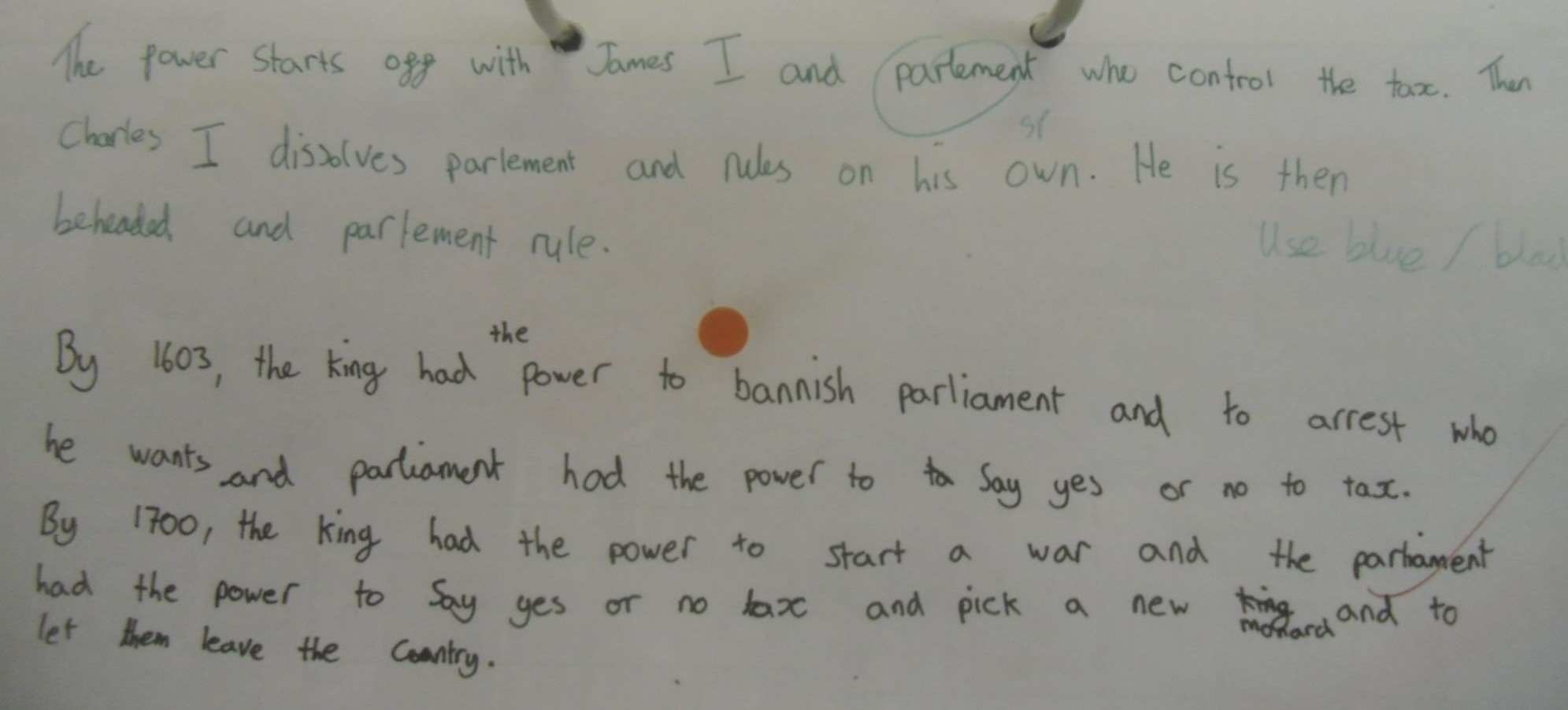

1) Students improve their individual answers. This should be implicit – but it shouldn’t be overlooked: the effect of repeating a task, new prompts, recapitulations and my checks mean that the second (or third) answer is almost inevitably more accurate and better articulated than the first:

In the process – and given that students are returning to the previous lesson’s resources, they may well be consolidating their understanding.

2) Students write better as historians, gaining familiarity with genres and conventions of historical writing.

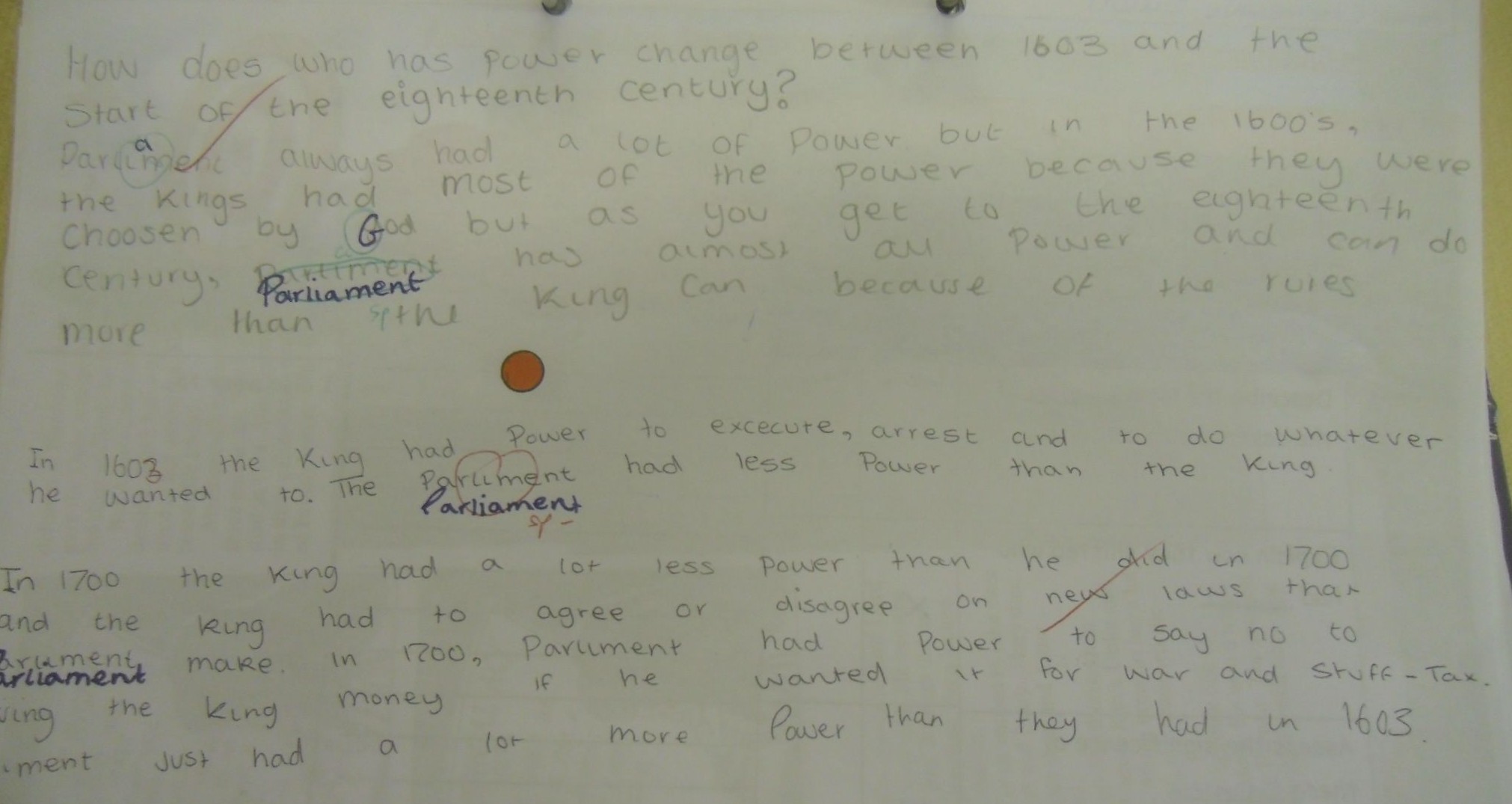

In the picture below, when examining the consequences of the events of the seventeenth century, the student has talked around the problem without truly tackling it. In her rewrite, she has explained the change more clearly, using a before and after structure.

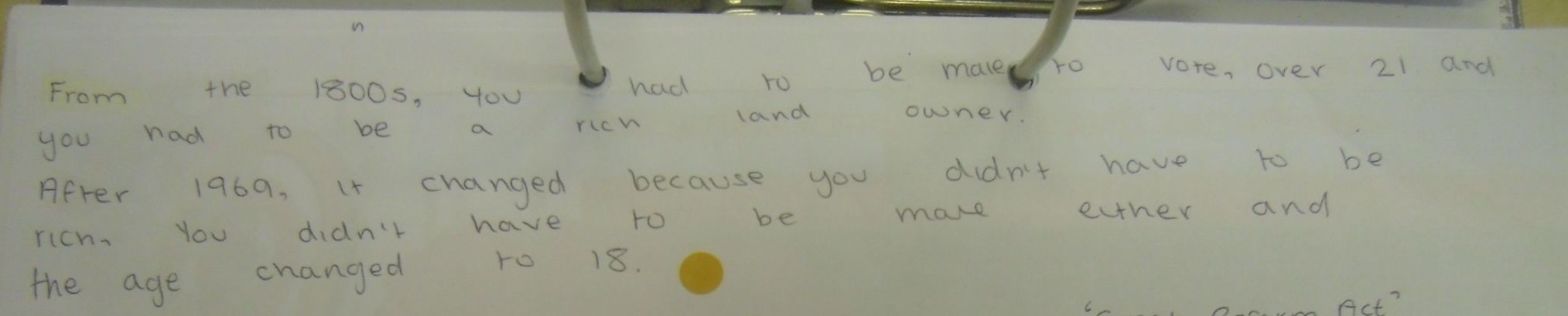

The next photo, below, shows the next lesson, which asked about reforms of the franchise. She has used the same structure to give a clear explanation – and, as a result, has progressed to the amber task immediately:

A colleague who saw this in action noted that giving students the summary task without any prompts or hints requires them to attempt to structure their answers unassisted (as exams and real life may demand). However, through the tasks given in the next lesson, this support can be reintroduced – so students learn the approaches required.

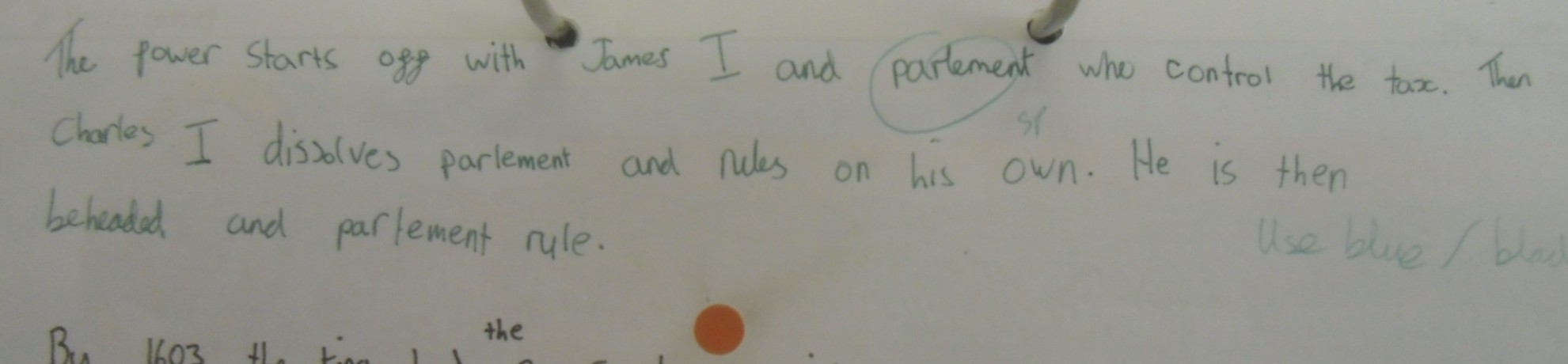

As well as learning how to structure historical writing, they also learn the minor but essential conventions of historical expression. To give an example, the student has changed from using ‘their’ to naming a king, and noting that the alliances Henry VII made came about through marriages:

This process has incorporated numerous similar examples, from writing kings’ names properly (‘Henry VII’ not ‘Henry the 7th’, for example – which may seem obvious, but takes some training) to adding examples and telling details, like individual provisions of Magna Carta or the Bill of Rights – all of which are part of the process of writing good history.

3) Students are able to write better. I’ve always struggled to see the effectiveness of marking isolated spelling errors, because they offer no guarantee the correction will be sustained. However, by doing this every lesson, I can keep reinforcing the required changes (capital letters, spellings, apostrophes) until they stick. A notable example was the correct spelling of ‘parliament:’ for one class, the second lesson saw twelve students spell it correctly and eleven fail to do so. Four lessons later, seventeen (of 21 students present) spelled the word correctly. (This could equally be as a result of reading the word repeatedly – but the number of corrections I made in the interim makes this seem unlikely!)

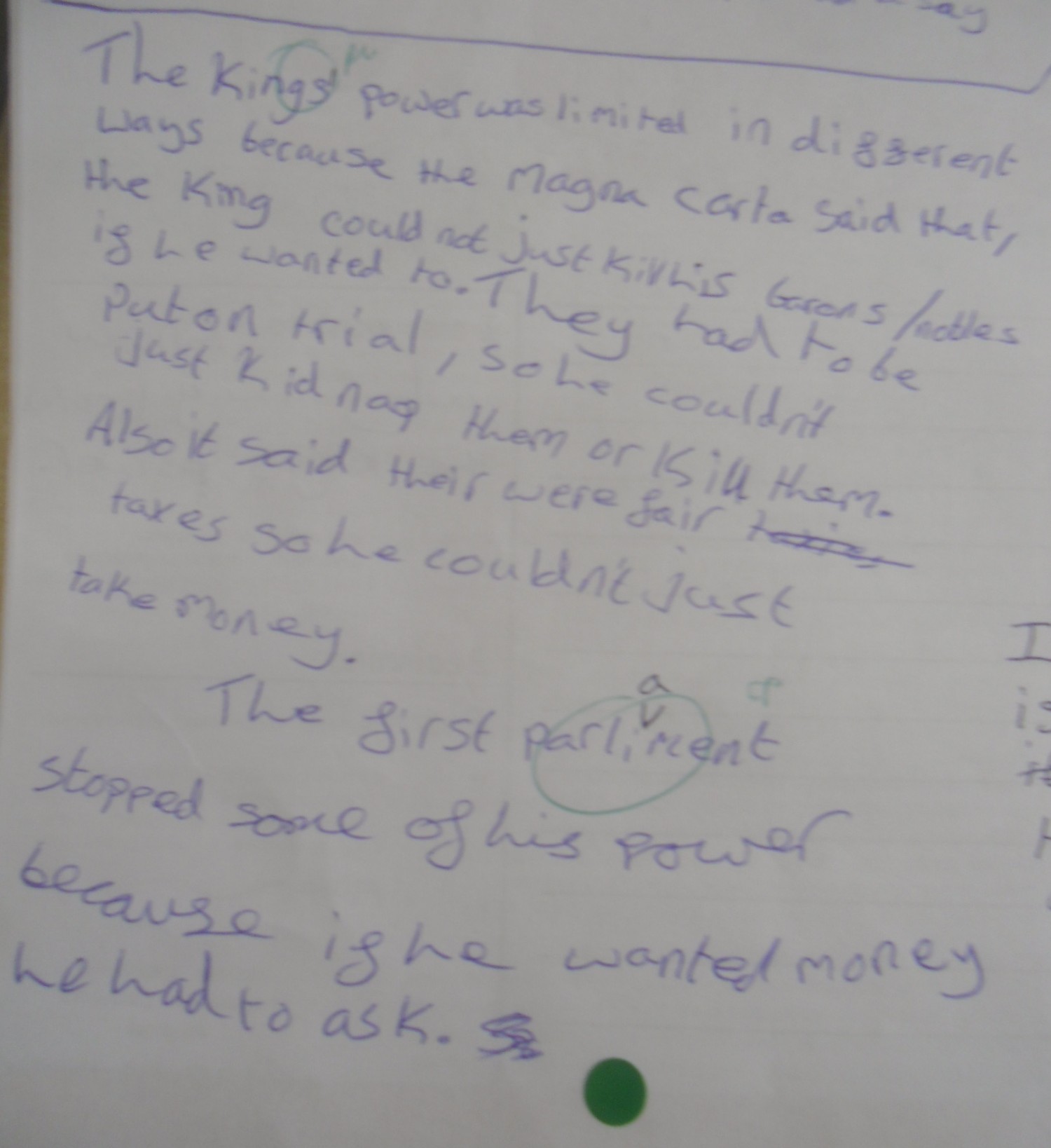

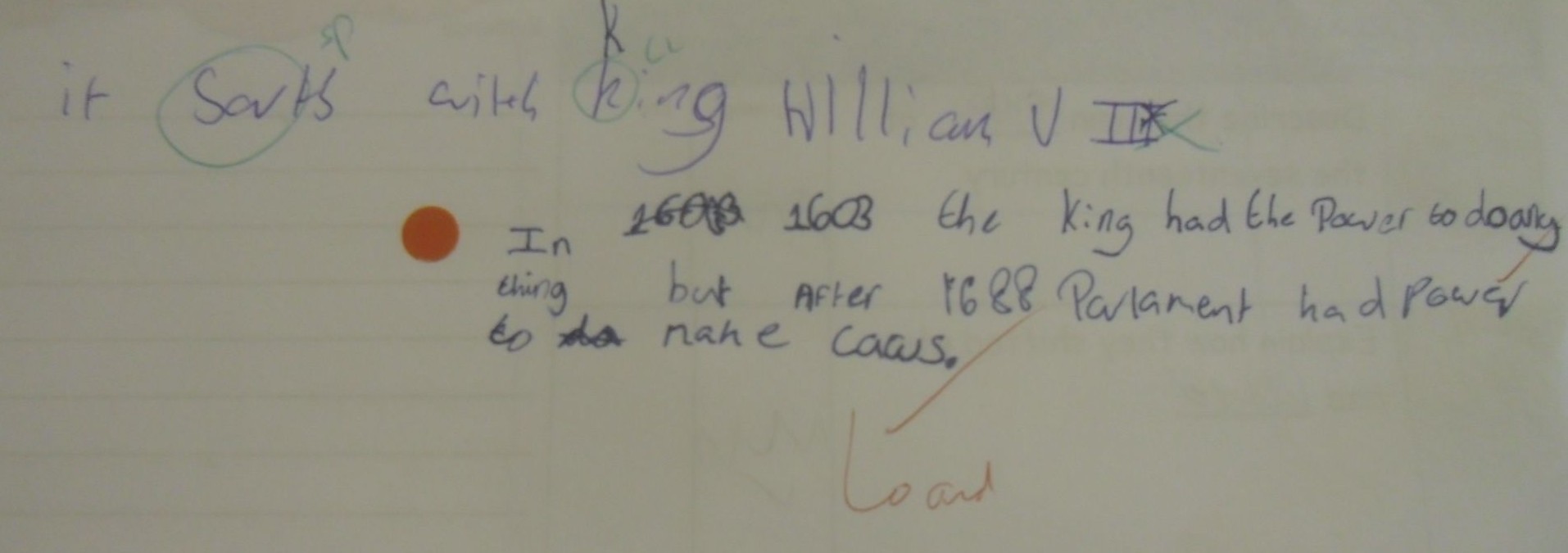

4) Students benefit from differentiated tasks every lesson. As someone who intends never to teach a streamed or setted class, this exercise helps to demonstrate how and why mixed ability teaching can work: all students tackle the same question at the end of each lesson, each student gets a differentiated task next lesson. Thus, while one student may be revisiting the most basic of concepts:

Another may be ensuring mastery of the first task (by adding the only missed point, castles) and then going on to think through the problems of royal power independently:

5) I have lots of genuinely interesting data. ‘Data’ is among my least favourite words: data collection in schools seems to entail taking useful information (a teacher’s knowledge of a student’s current performance) and transforming it into a level or grade which confers little meaning (but to which much weight will be attached). This, on the other hand, is meaningful, fascinating data, making visible students’ progress each lesson. I can identify and assist those who are consistently struggling – more potently, it seems, I can identify the lessons or concepts which my lessons have failed to unravel – and adapt my teaching accordingly – it was clear that the seventeenth century had entirely baffled one class, for example. This is data in something close to ‘real time’ – rather than waiting for a drop in sub-levels next half term, I can identify confusion and act immediately.

6) A better culture of learning. This point is more wooly than the others – but remains a potentially powerful consequence of this marking approach. This repetition confers many benefits: students are asked to do the same thing twice, and so get two ‘bites of the cherry,’ two chances to understand each lesson. They are thus closer to mastering each concept than they would previously have been – and have shown greater cumulative understanding and ability to recall and discuss these ideas intelligently, and plan essays which I look forward to reading. Reflection upon and improvement of work become routinised. I have always had students recap the previous lesson’s (or lessons’) work – but this method entails deeper thought and effort than the simpler tasks I had provided previously.

Is faster better: Should we really be giving more feedback?

Perhaps my favourite Art on the Underground poster quoted Gandhi thus:

There is more to life than increasing its speed.”

Whenever I saw it I was torn between appreciating the point made and the irony that the organisation charged with getting us around London swiftly should employ this. Gandhi (or the artist, perhaps) raise a worthwhile question though: does shaving three minutes of the end-to-end journey time of the Victoria Line increase human wellbeing (or even economic productivity)?

Having outlined the many ways in which it seems that reinventing the wheel and increasing the frequency of feedback may have helped my students, it’s worth stepping back before deciding that it’s a good idea. Two powerful, recent posts, from Andy Day and David Didau, have laid out a number of criticisms to the current cult of feedback. Their points are numerous, thoughtful and well-evidenced, so I won’t attempt to fully enumerate, let alone refute them. I suspect anyone refining or increasing their use of feedback would do well to attend to their points, much of this evaluation is written in the light of their writing.

Time: Andy is “hugely concerned at the increase in marking load that has been expected of teachers over the last 18 months…” This method is quick: even with literacy marking, stickers and tracking, I rarely take more than fifteen minutes over a class set of work. My planning time is actually diminished as well: I know what both the concluding task and the DIRT activity will be as a result of my marking.

Opportunity: Everything has an opportunity cost – as John Blake mentioned to me recently, people are very poor at reflecting on this, because it is often hard to identify where this price is being paid. I had planned to employ hinge questions before students began writing – I soon concluded that there wasn’t time to do both well. Likewise, the two or three hours a week spent on this is time not spent on something else (I’m not entirely clear what). Marking everything quickly still takes longer than marking some things quickly – my previous practice.

Timeliness: Both Andy and David reflect on the contradictions in the evidence on the timeliness of error-correction. Swift feedback is helpful; while too swift feedback can undermine learning (or time spent on the task). I won’t pretend to have begun to approach this problem with the depth and thoughtfulness they have. I have wondered whether the hinge question vs. writing and marking dilemma perpetuates or extends errors from the lesson. I’m inclined to say that the individualised feedback and DIRT time makes this strategy a better one… but I have no way to be sure.

Mastery: This is nearer mastery learning than my previous efforts. Reviewing the photos above demonstrates the continuation of some mistakes – or weak explanations, which I’ve overlooked in my second marking… I still don’t have a way to ensure students master every concept or aspect of content. The differentiation helps ensure all students can come closer to full understanding.

Remaining questions: I’ve not yet thought through whether this feedback is so frequent it builds students’ dependence. Nor have I truly addressed how students perceive the stickers – whether as evaluative or (as I see them) focussed on the task and the next steps.

Conclusion – it rolls: let it go.

This said, and with the likelihood of confirmation bias acknowledged, I think there is much to be said for this approach. I am better informed, my students are closer to mastery and are writing better history – and all my books are marked up to date, a position I have never been in as a teacher. I’ve begun developing a similar approach for my Year 7 classes too.

Update

Further reading

The posts by Andy, David and Joe cited above are well thought-through, finely argued and most worthy of consideration.

The debt which this post owes to the writing of Alex Quigley and David Didau more broadly is probably obvious: as I was writing I was thinking most frequently of Alex’s writing on DIRT time and David on marking as an act of love.

Mr Benney has written an incredibly thorough, lesson-by-lesson account of introducing a similar system with a Year 11 class.

Finally, for an entertaining take on whether we should be making train journeys faster, or spending our money elsewhere, try this.

Thank you for this interesting post. I am trying to work on a (less ambitious) version of the same in my own lessons/department. I agree re many of the ways it is beneficial. One thing I struggle with is that there is an additional opportunity cost within lessons; increased time on DIRT is reduced time on other material. For example, if we spend 15 minutes (roughly) on DIRT in the lesson, there reamins roughly 30 minutes for the rest of the material. By the time I’ve introduced and taught a concept, allowed some quick practice on MWBs (it’s maths, so different), checked for misconceptions, and then set them off on a suitable task, there’s little time left for meaningful practice, or to progress to really challenging work that will expose where gaps are. How do you reconcile that particular opportunity cost? Sometimes I worry that a key reason a pupil is amber/red is that I simply didn’t give them enough time in the previous lesson; time they would have had had I not enforced DIRT! This is obviously a very cynical reading; I would be interested in your views on it.

Thanks for the comment: this is a problem I should perhaps have explored in the post – and I don’t think it’s at all cynical! With a couple of lessons I found that the DIRT took so long (because students had struggled with the previous lesson’s ideas) that it was over half-way through the lesson when I introduced the ‘main’ focus of the lesson – and I certainly think that on occasion students got red or amber stickers simply because they lacked time to finish the end of lesson summary task. I’ve chosen to look at things the other way around though: we can assume that, if we didn’t take this approach, students might have spent 45 minutes practising in one way or another in one lesson. This way, they still spend 45 minutes – 30 in the first lesson and another 15 in the second. But the second attempt is done with the benefit of feedback – and by being split between lessons, it is more likely students will retain what they have learned. That’s how I’ve reconciled myself to it anyway. What do you think?

An intelligent, articulate and downright excellent blog. You’ve struck gold again Harry. Your statement “this exercise helps to demonstrate how and why mixed ability teaching can work: all students tackle the same question at the end of each lesson, each student gets a differentiated task next lesson” is perfect and I can’t help but smile when I read it (being a big advocate of mixed ability groupings). The beauty of this differentiation is that is is not based on preconceptions of the pupils; it is based on their output at the end of the previous lesson and nothing more.

Your method of marking (including literacy corrections) the summary question shows that this marking can be efficient on time and lead into the next lesson. Marking is certainly planning.

Like yourself, I am slightly concerned following David’s blog and the question of whether students will get dependent on it. Like you though, I feel it’s working so I’ll let it roll.

I am certainly going to re-read this blog a number of times to see whether I can pick up tips to make my marking method more effective. I am sure there will be. I will also be imploring all my colleagues to read this. Whether you’re reinventing the wheel or not, the wheel you have created looks outstanding and I am sure your pupils appreciate it and will make better progress because of it.

Damian

Thank you for the thoughtful comment – and a good deal of the inspiration behind the post (I reread yours yesterday as I was drafting this)! I completely agree that this kind of differentiation offers every student the greatest scope to move on unconstrained by my or their preconceptions.

Reblogged this on Excellence & Growth Schools Network.

After being impressed by the ideas in the post (and other posts you have written) I wondered about a couple of practical questions. Firstly, how do you deal with students that missed the previous lesson(s)? Is it as simple as printing out a copy of the follow up tasks for the last lesson they attended and then skipping to the new lesson question? Secondly, considering this in conjunction with the ideas you posted about sharing learning intentions, do you recommend students to have exercise books or folders?

Hi Meg,

1) If a student has missed one lesson, during the time other students are making improvements to their work, I’d usually give them the sheet from that lesson and ask them to complete the ‘red’ task (I see that as another advantage – by spreading the ‘lesson’ across two lessons there’s a second chance implied). I also had an introductory lesson giving them an overview and a ‘revision’ lesson at the end going back over it, so if they missed several, I would use that as the point to catch up.

2) I’m really keen on folders – for convenience, for the ability to hang on to work across a year and between years, for ease of being able to take a hundred pieces of paper to mark not a hundred books and so on. That said, creating a system to ensure all students keep the folder in order was a bit of nightmare and inspectors struggled to find their way around them, which contributed to our woes at inspection. So my preference would be folders for the long-term benefits, but books are probably a lot easier in the short and mid-term.

Thanks for the swift reply. Enjoy the long weekend!