The awkward gap between leaving one flat and moving into another has been alleviated by kindly benefactors with a spare room; it is only ten minutes from school, (my old flat was forty), which, when you’re cycling and the temperature is around freezing, is quite an advantage. The flat has another special feature, justifying this aside: the shower curtain, which shows the periodic table:

There is an opportunity in every challenge, apparently; a stalled move offers the chance to learn the elements. After GCSEs I dropped studying science in school and in life; I remember a few bits of chemistry, but it’s very patchy. The effect of daily practice of the periodic table mirrors that which Kris Boulton described when memorising ‘Ozymandias,’ and has led me to a series of questions: What is atomic mass? What do the columns mean? (Why is hydrogen in the same column as a number of fast reacting metals?) What makes an element radioactive?

Kris is one of several bloggers who have been extending the case for ‘knowledge’ and considering how and why improving our memory of what we are learning is important. The way in which bloggers, notably David Didau on the power of knowledge and methods of retention and Joe Kirby on memory, have built upon the foundations laid by Daniel Willingham, has led me to consider more critically what I’m doing to help my students retain what they have learned. This post explores three techniques I’ve been using over the last half term with the explicit aim of ensuring better retention, in the short, medium and long term.

Three activities to build retention

1) Short term: lesson-to-lesson or through a scheme of work

One thing that has depressed me as a teacher has been asking a question covered in the previous lesson and being met by a deathly silence. Part of this lies in improving the design of the previous lesson; equally, we must accept that we begin forgetting things as soon as we’ve learned them. This activity does the opposite: we return to the same activity every single lesson until we reach some kind of mastery.

I wrote recently about the centrality of chronological understanding in history and the limited nature of the proposed solutions. This unit was designed to address some of them and to provide what I described as a ‘mannequin’ as a framework from which students could work. I selected ten years which represent either critical moments in British history or offered some kind of archetype for the period. I assembled two A4 pages which summarised: the era’s name, ruler(s), events that year in Greenwich common household objects, Britain’s then wars (or, occasionally, peace), population and life expectancy. war or peace, books, population and life expectancy. The lessons thereafter were pretty simple:

– ten-fifteen minutes on a card sort* during which students linked together each individual piece of information (so, for example, they could place 122 with ‘Roman,’ the visit of the Emperor Hadrian to Britain, the building of a temple in what is now Greenwich Park and so on).

– thirty or so minutes working on a timeline which represented this information (and will provide a resource for the rest of the year)

– ten-fifteen minutes with students asking me questions based on the information they had been working and thinking about

What does this achieve?

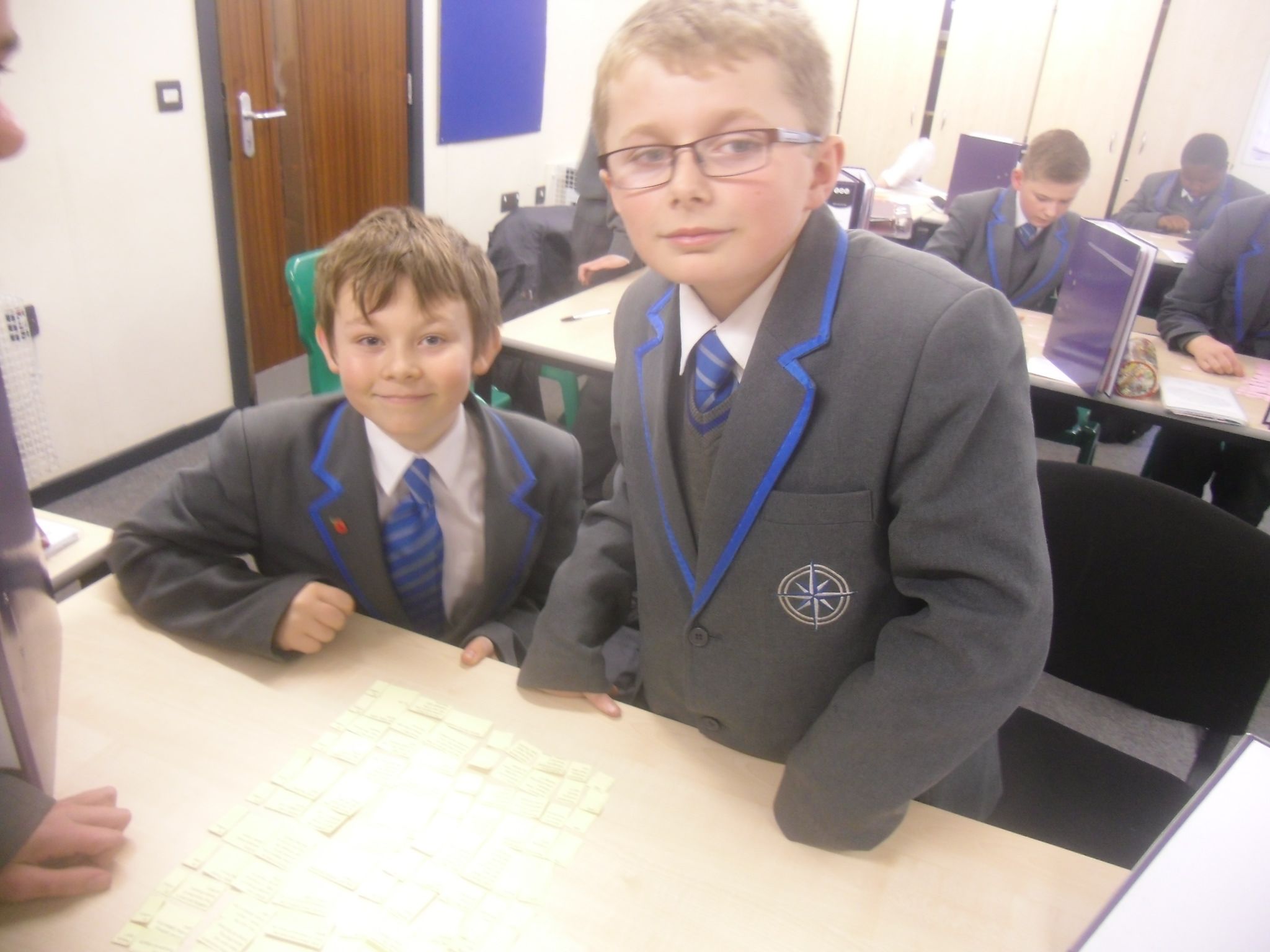

Before: the early moments of one pair’s first attempt is shown below:

1215 1533 1675 1776

Anglo-Saxons Normans Romans Tudors

After: The pair below were the first to place every single card (eighty, I think) in the correct place.

And this is the first completed timeline:

The card sort activity is, in essence, a repeated, low stakes ‘test,’ the practice offered by repetition means that the information involved is gradually committed to memory, a process which is reinforced by representing this visually on the timeline. Students recall is improving significantly; I was asked a question about American independence in a recent lesson and I answered it and asked, in return, when was that? The student involved struggled briefly with the date and compromised: it was in the time of the ‘Hanoverians – George III.” This growing familiarity benefits everyone, but especially, I think, those whose pre-existing historical knowledge is weaker.

This simple approach makes for some good lessons in a couple of ways. I took time to ‘sell’ this appropriately, but, slightly to my surprise, most students have become increasingly keen on doing this – settling into some kind of race on the card sorting, happily drawing and questioning. For me, it is also relatively low effort, high impact; barring checking and feedback (of the ‘you have two cards out of place’ variety), I have had a chunk of lesson time freed up, much of which I’ve used to spend going through students’ folders of work and providing individual feedback. Some students are less engaged than others, but certainly no more so than in other more purportedly ‘engaging’ lessons of mine.

Even a few months ago I’d have kicked against teaching time being spent on the ‘recall of facts,’ which is what much of this activity represents. Facts are useless and dull in isolation – my opinion is little changed on this point. The important thing is that they are not in isolation: Charles II is linked with the foundation of the Royal Observatory and a period of rapidly growing population in England, and we’re already on really interesting ground. I think this activity has been useful and challenging in three ways:

1) This strong knowledge of these years is a framework on which we can build. Choosing only ten years was really tough – it is just an outline. However, in future I can use this as a reference: we know the population in 1776 and in 1885, give me an idea of what it must have been in 1832. The same people reappear throughout history (or can be made to): at our recent trip to the National Maritime Museum we examined the foundation of the East India Company, chartered by…? Elizabeth I (born at Greenwich Palace in 1533, one of our key years). A ‘household object’ in 1675 (in some households) was sugar: and suddenly the impact of the empire and slavery is brought to life. As we study the history of Britain, the empire and slavery during the rest of the year, my students will have a strong basis from which to work.

2) The knowledge of these facts is a strong basis for fascinating questions. Joe Kirby mentioned yesterday that increasing knowledge leads directly to more questions and greater curiosity. The highlight of each lesson is question time at the end – I wish I’d written them all down, they’ve been brilliant. From the driest of information, estimated population statistics, profound questions flower. Why did population collapse from Roman times to Anglo-Saxons? (Trade and social organisation, it seems). Why another huge fall during the Middle Ages? There you have the catastrophic effect of the Black Death; suddenly, the awesome effect of losing 40% of the population hit my students. Why doesn’t life expectancy change significantly until Victorian times? The impotence of medical advances before the late nineteenth century are now transparent. What are barons? Why does the king need barons? Couldn’t the barons just rebel…? The stage is set for Magna Carta. The depth of the questions and the sense which the answers make for them relies on students’ knowledge and understanding.

3) Everyone has to finish the timeline, so there is ample time for challenging ‘extension’ work for those students who have worked more quickly. I’ve invited them to choose from a range of topics: linking with other schemes of work (maths, empire, British political history) or to choose a theme that’s missing, or simply to investigate the information that’s missing. With the strong framework and knowledge basis, I am confident to leave this extension much more open.

2) Medium term: teaching, testing, retesting

In my former school I got into good habits with my Year 11s of creating frequent mini-tests, with time to recap the topics and then a repeat of the test. I built review lessons into my plans for the curriculum at my new school and then allowed myself to get carried away by the momentum of teaching and didn’t use them frequently.

This year, influenced by David Didau’s summary of the research on the effect of testing (it’s more powerful than reviewing), I decided to go back to this but to focus much more on the tests (and the effect of repeating the same questions throughout the year). The structure (thus far) has again been very simple, collecting questions which summarise the most important points we’ve learned over about half a term, and then:

– students complete the test

– they peer-mark (using an answer sheet I provided)

– they make their own corrections using the same answer sheet.

What does this achieve?

At the first outing, not a huge amount that’s measurable. It has given me some interesting supplementary data (which hasn’t taken me a lot of time marking – I just scanned and recorded numbers correct). It provided a chance to recap what we have covered. I don’t have a control group, so I can prove little at this point.

Where it should become more interesting is in the next mini-test, when I repeat some of the questions from the previous test (such that all of the questions are repeated at least once throughout the year). Even more so, when students in Year 8 sit down to be asked questions about Year 7 work. This is how we will beat the ‘forgetting curve.’

I also suspect that it has had an impact on students’ ideas about what they should be remembering. The test is meant to be low-stakes – I’ve explained the forgetting curve (briefly) and that this is also a compensation for perhaps not fully understanding something first time or being away one day. Nonetheless, the power of the implicit message was made clear to me by the (separate) responses from two lovely Year 7s to the first test:

A: “You didn’t tell us you expected us to remember it.”

E: “But I was away when we did some of these questions so it’s not far to ask me about them.”

When I told them that Year 8 would be tested soon on what they’d learned in Year 7 they looked astonished (and slightly appalled). I can prove nothing, but I wonder whether knowing that you are expected to remember things (not just being told this) might lead to increased attentiveness and effort first time around?

So, it’s too early to claim strong conclusions for what I’ve done – but it feels right and it accords with the research, so I’m optimistic.

3) Across a key stage/school career: the spiral curriculum

I’ve written before about the lack of time for history in the curriculum and the ruthless choices we must make in consequence, I suspect that the twenty minutes Year 7 spent on Ancient Sumer and Assyria this week is going to be all they get on those topics. With time this short, what sense does it make to teach some topics twice?

Yet some things we will cover several times, most notably (again) periodisation. Year 7 are currently spending a lesson in each key era, while Year 8 are examining individual years in substantially more depth. In Year 9 we will come back to these eras again (I hope, through the lens of examining how each period viewed Julius Caesar). This repetition is designed to increase the likelihood that students retain and develop their sense of this chronological framework. Much like the first activity, it is also a way of broadening and deepening students’ understanding of the periods, by revisiting them with a stronger historical knowledge each year.

Evaluation

If I were to summarise this post in one word it would be ‘repetition.’ With more words, I would elaborate on repetition, and use terms like: ‘interleaving’ and ‘distributed practice.’ These are powerful techniques; to access them I’ve had to overcome some deep-seated and instinctive hang-ups, for example, that doing the same thing more than once is boring, fruitless and alienating.

In my experience, it almost always takes longer for a group of students to pick up and thoroughly understand something than I would anticipate. I may believe we’ve ‘covered’ that, but many of my students may still be getting a grip when I think it’s time to move on. Repetition really helps to provide time and space to ensure that they do really grasp what they’re learning. What if they get bored or do find it easy? Well, that’s fine, if they can prove they’re ready to move on (by completing the card sort and the timeline, for example), I have a raft of ways I can push students further.

I wonder if repetition and the success this offers may also have a significant effect on students’ ideas of learning and themselves. I referred above to the links between Queen Elizabeth and our museum visit recently; I asked in the trip booklet:

Who gave the East India Company it’s charter?

(Link with our recent lessons) Where was she born and when?

The latter question could only be answered from memory, not from the gallery concerned. I was with a group of three students when one student recalled this detail. As I walked away, I heard him turn to his friends and say something like:

I’m really smart in history at the moment you know.”

While I’ve been going back on my convictions, so has he: he’s said the opposite to me in the past. Again, I’m longer on assertion than on proof here, but I have a strong feeling that the repetition and consequent mastery he has attained are what have given him this belief.

People enjoy mental work if it is successful. If schoolwork is always just a bit too difficult for a student, it should be no surprise that she doesn’t like school much.”

Daniel Willingham, Why Don’t Students like school?, p.3

Many of my posts spend more time on limitations than on anything else and yet this post is light on them. What are they?

I need to work more on understanding memory and retention and experiment better with these techniques. I’ve never taught mnemonics (although I’ve used them to help individual students). I need to spend more time on the cognitive psychology underlying this.

I need to follow through the curriculum design and plan more clearly with GCSEs (particularly) in mind – I’m trying to ensure a broad historical understanding (and I don’t know what the new papers will look like exactly) but there’s more planning backwards.

And do students dislike it? One or two have complained (or made their complaints clear). That’s pretty low (from a hundred)… students have become more keen on this over time, rather than less so, and have absolutely loved the extensions if they’ve got that far.

But beyond that, there are remarkably few limitations that spring to my mind.

*I know card sorts have a bad name in certain circles. I’d point out that 1) our curriculum assistant made it and 2) even if I’d made it, given that four classes got ten (or more) minutes a lesson out of it over several lessons it paid its dues.

Further Reading

Numerous people write interestingly and well about this, but these three have influenced me most on this:

Joe Kirby, on cognitive science and on memory.

Kris Boulton, too many interesting posts to reference separately, so here’s a link to his blog instead.

David Didau, on learning, performance and memory and on testing.

I’ve written about Willingham’s book before, exploring and critiquing some of the ideas and arguing that his prescriptions demand that we consider the literature on teacher change. While I think some of my initial points stand (something Willingham concurred with in his own comment on the first post) my recognition of the importance of what he’s arguing has grown over the last few months – as I partially described here.