Why is history in the curriculum?

I’m not being rude but it doesn’t actually help you in your daily life.”

To punish people.”

So if anyone asks you a question you could answer instead of saying I don’t know.”

(Quotations from students in Richard Harris and Tony Haydn, ‘Children’s Ideas about School History and why they matter’, pp. 45-46)

Not all student responses looked like this, but these individuals’ words exemplify a problem: although 70% of those questioned claimed history was useful, fewer than a third were able to articulate why.*

It is possible that the absence of a clear and developed understanding of why they are learning about the past, and about the discipline of history, is impacting negatively on pupil effort and attainment in history, and on take-up rates post-14.”

(Ibid., p. 48)

A few months ago, noting that motivation correlates with attainment and GCSE choices, I argued that demonstrating the relevance of history to students is important if they are to immerse themselves in learning and recognise the subject’s importance. In that post, I mentioned having spent a year working on this problem with a Year 9 class. This post describes and evaluates my actions and their reactions during our first term together, as I tried to persuade them that history matters.

Who better to explore this with than Year 9 (thirteen/fourteen year olds)? In most schools this is their last year of compulsory history, so it is critical in cementing their understanding of the past. Most students are pretty confident at the beginning of Year 9 whether or not they will choose to study history in their GCSEs; the majority conclude they will not (nationally, a third of students study History GCSE, figures replicated in my former school). History is a hard sell: a large proportion of students see the subject as difficult and irrelevant to both everyday life and their future careers. Moreover, Year 9 is the dip: equidistant from the bright-eyed enthusiasm of entry into a school in Year 7 and maximum pressure from school, parents and usually, students themselves, in Year 11. Proving history matters is a challenging task in this context, but a vital one.

What did my class think of history?

I was teaching a mixed ability class; most of the students were new to me – if we can overlook a disastrous cover lesson I’d had with a third of the group the previous summer. The head of year was characteristically upbeat, noting that “You’ve got a very bright class here” and saying less about their fairly unenviable behavioural reputation. She did mention that a couple of parents had never heard anything good about their children and if I managed to ring home positively early, it would be worth my while.

At the end of our first lesson together, I asked students to answer: ‘How do you feel about history? The picture below shows my summary of reasons why students said they didn’t like the subject:

Above all, they expressed the idea that it was ‘not useful’ or ‘irrelevant to my life’ and ‘boring,’ a word which came up more than any other. Only four students had anything positive to say about the subject… it seemed pretty clear to me that embarking on the (pretty dry) prescribed course was unlikely to achieve anything.

There is sufficient evidence of school or departmental effect in the data to suggest that teachers can have an influence on pupils’ understanding of the purpose of school history.”

(Ibid., p. 47)

My goal was to teach students to love history and to recognise its profound importance to their lives… but I believed this was something they had to realise for themselves. So I began by asking:

What questions matter to you?

I began with the still on the right from from the Italian Job and asked students what questions they would wish to ask about this picture – they came up with a good range: What had happened? Was the driver drunk? And so on.

I then developed an idea from Teaching as a Subversive Activity and asked students to imagine that they were redesigning the school curriculum from scratch, without reference to tests or syllabuses. What questions would they want answered in such a curriculum? I was nervous at this point as to how well they would respond to the idea; results varied, this is a representative sample:

- If you were in a fight with one of your friends and you seriously hurt them, and no one saw you, would you take them to hospital or leave and pretend nothing every happened?

- How did music emerge as a global phenomenon?

- Why is there school? Why do we need education?

- Can you explain global warming?

- Is there something you can’t live without?

- What do you aspire to be in the future?

- Would you give your life for people you care about?

I closed by returning to the list of questions about the bus and asked what did almost all of the questions refer to? The idea I was trying to convey was that we have to look to the past for answers to every question except one (what happens next?) we can predict an answer to this based on all the other answers.

How can history help us answer the questions that matter to us?

I wanted students to see how a historical question can help answer a philosophical or ‘life’ question, so I began with an easy example: one student had asked ‘Is Arsenal rubbish?’ so I invited students to break this down into smaller questions (for example, how many goals did they score last season?) They then extended this to formulate historical questions which helped answered some of their other (more interesting) questions. I also offered them some of my own historical questions (ensuring there was at least one historical question linked with each philosophical question); examples which linked with the questions I listed above included:

- Why did the Victorians let children not go to school?

- What did Roman people think you couldn’t live without?

- What did the Ancient Greeks think was the meaning of life?

Finally, students voted on the question which they most wanted to research.

I wrote to a friend after this lesson: “I’ve been reading their books and from the last lesson some of them did write stuff like – now I realise the past can help us understand other questions… so I think it can work.” And as another friend said to me at the same time, my having promised to prove that history mattered and let them choose their question “You have to honour that!” I was unsure where things were going, but it looked like the right direction. So I prepared to help my students answer their question through history.

‘Are you a leader or a follower?’

This was my students’ chosen question, and it was a gift to a history teacher. I designed a lesson which explored this question from a range of angles: looking at why so many people voted for the Nazis, what made leaders like Martin Luther King and Gandhi successful and, by my students’ request, how fashion trends spread. I also asked a wonderful Year 13 Psychology student to visit the class and explain Stanley Milgram’s ‘Obedience to Authority’ electric shock experiments. Students spent a lesson examining these different examples of leadership & following and at the end, I asked them whether they were leaders or followers based on what they’d learned.

Over the next two lessons, students created presentations on different aspects of what we had learned: how we had got this far, what history suggested made a leader and a follower, what we had decided about ourselves and the skills we had developed. They then presented what they had done to the head of year (and I had it filmed as well).

Other ways of demonstrating relevance

Although the hardest bit of the ‘selling’ process was over, I devoted the rest of the term to continuing this push. We looked at propaganda as a tool during World War I – and applied this knowledge to modern advertising. We worked on essay-writing and persuasion – as a tool for history and for life. And we studied the origins of the London riots (one of the highlights of this was Zelal popping into a police station, on her own initiative, to enquire into the racial disparities in arrest statistics). At every point, I devoted time to the ‘so what’ question – underscoring the importance of what we were doing.

In the spring term I pushed the class to create far better work – which matched their interest in the subject, rewriting essays and seeing some great essays from some of my students. In the summer I focused on sharing what we’d learned and organised a trip to a local primary school to teach them what we had been learning, in which every student had a role presenting, teaching or supporting Year 6 students. Again, every topic we studied or skill we refined, I set time aside to consider why it mattered.

The results

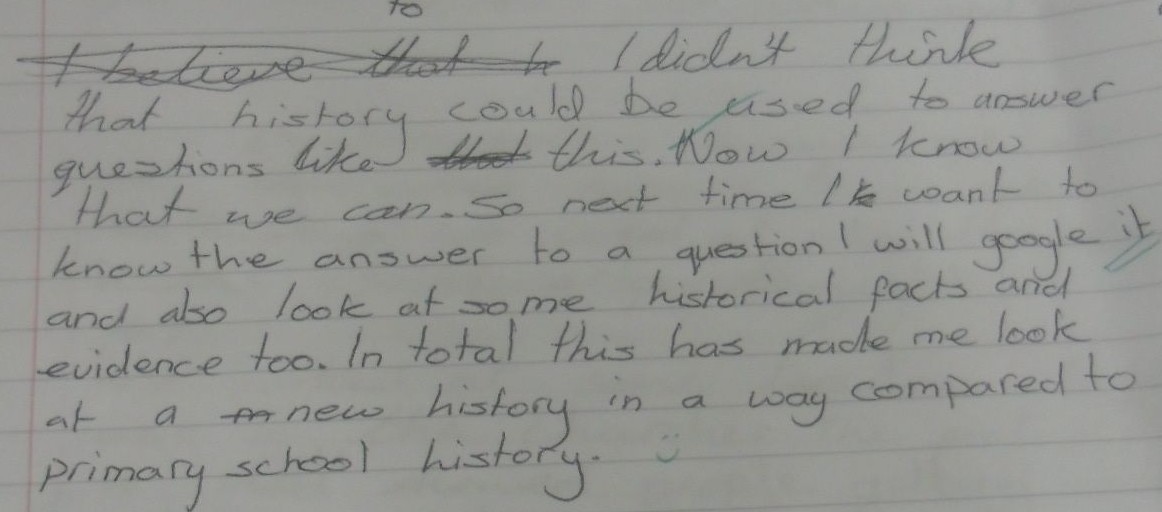

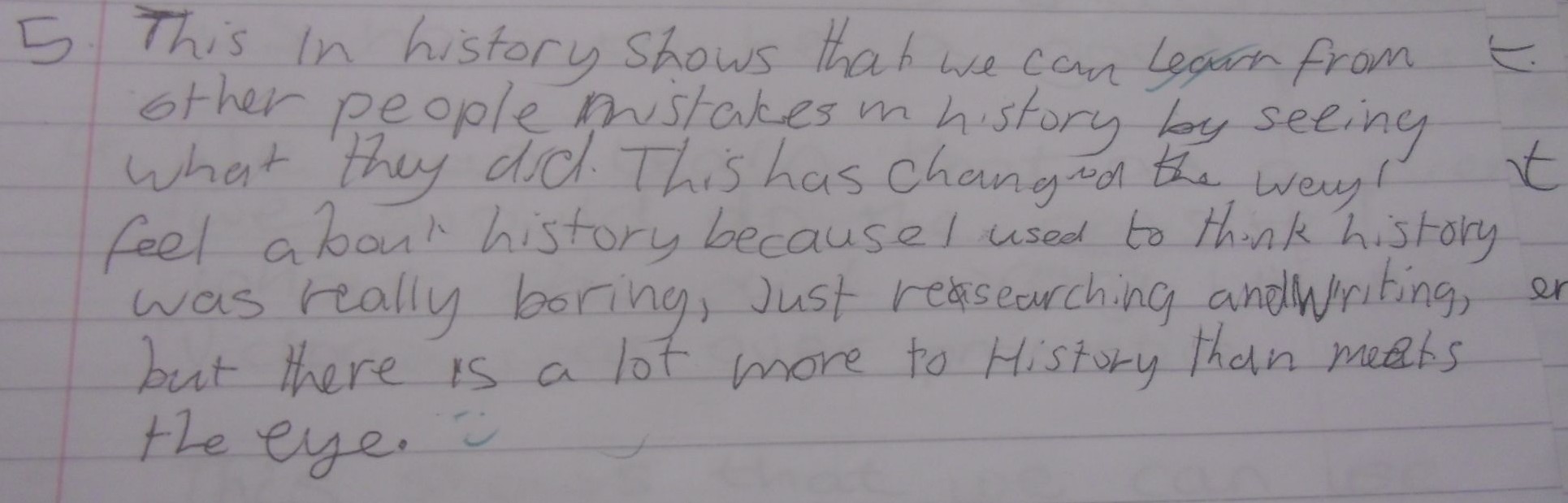

Avowed beliefs: In January asked students to write postcards addressed to my Year 9s next year which summarised why history matters (as I explained, to save me the time of those new students misbehaving before they recognised why the subject mattered). The gallery below shows their responses- but the other noteworthy factor is that no one refused, no one said ‘I don’t know what to say.’ No one wrote nothing – so all of them had gained some impression that history was useful.*

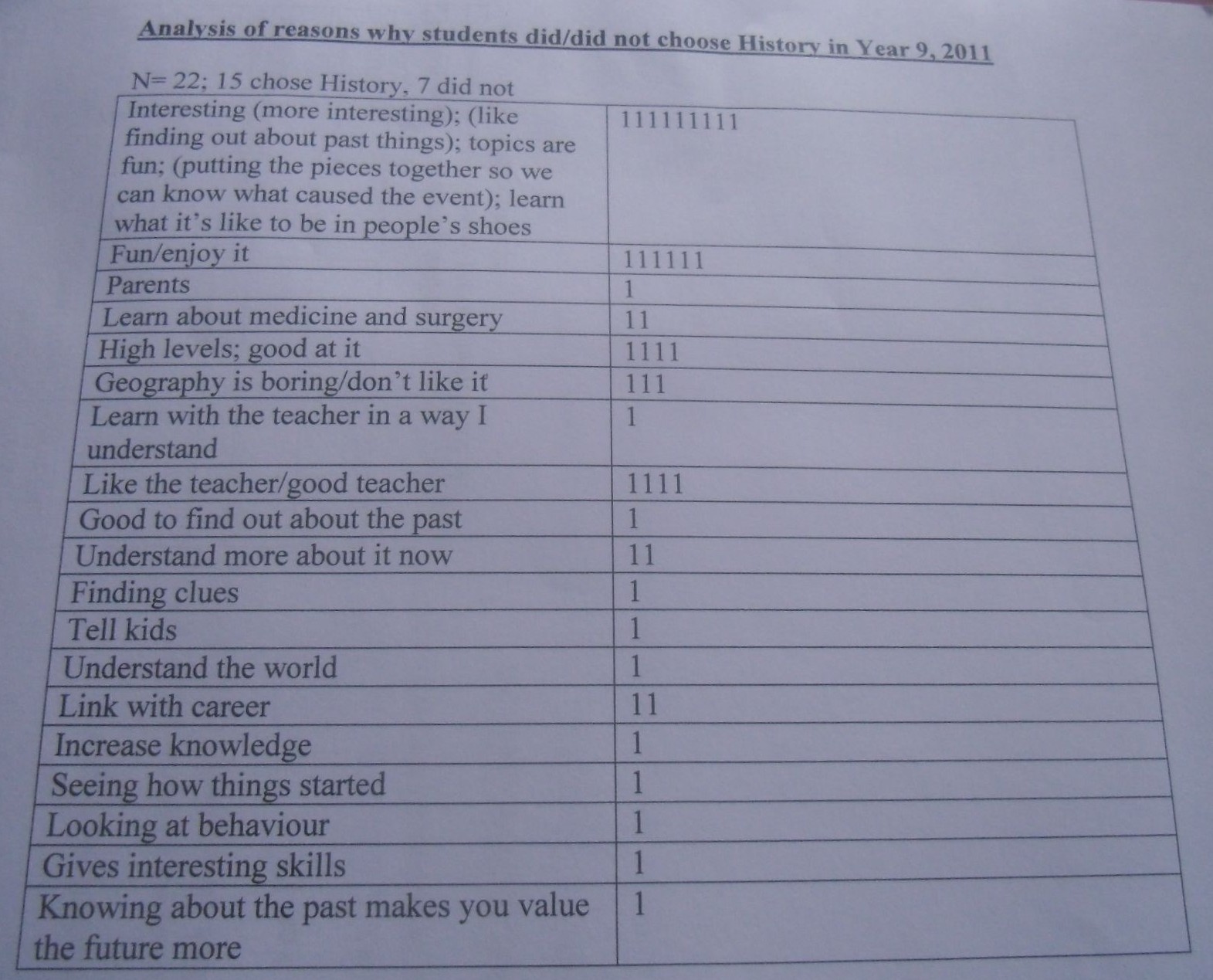

Choosing History GCSE: When it came to their choices, seventeen students chose to study history and seven didn’t – a rate which was three times the school average. I asked them to explain to me as best they could why they had chosen history; my summaries are below (some students made more than one relevant question):

(Two students were absent on the day I asked this question, both of whom had chosen history).

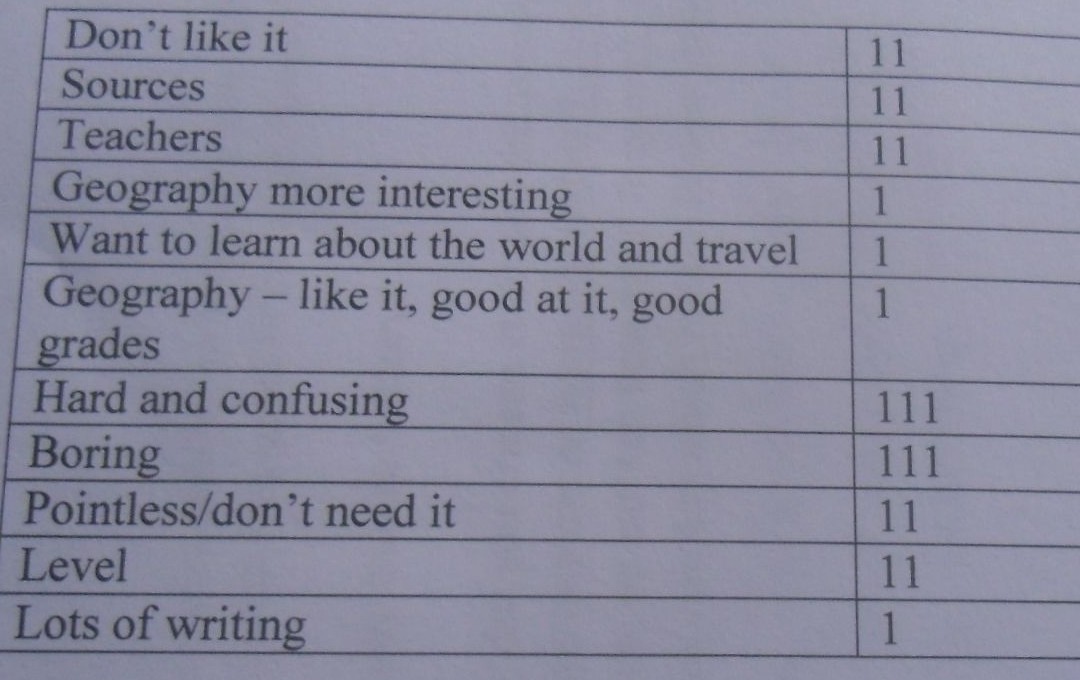

And as to why they hadn’t…

And, if you’re particularly interested, here are their responses:

Academic results: I received some absolutely brilliant pieces of work – the highlight being the student who moved from apparently being on level 3 to level 7. That said, a handful of students made no progress on paper- primarily because a cunning combination of absence, time in the school’s behaviour unit and avoidance of homework meant I barely saw any of their written work; that said, I should have done more to chase those individuals.

‘Prosocial behaviour’: This one’s harder to evidence, but students displayed better attitudes to learning and school more generally. Firstly, I ceased calling for help from my head of department/form tutors/the head of year/school behaviour unit, because off-task behaviour was sufficiently limited, and relationships were good enough, that I could address this unaided. This was a novel situation with me for an entire Year 9 class – every previous year we reached a point in the summer where one or two students had adopted such a consistently negative attitude (and had long since chosen not to study GCSE History) that they were removed entirely from history lessons. More tentatively, I would argue that there was a power in students having a subject which they enjoyed, succeeded in, had a teacher to say something positive about them in parents’ evenings… I don’t know what it counted for in their wider lives, but I do know that one parent claimed she dropped the phone when I rang to say her daughter was doing well (first positive call home ever). The same student (who was a bit of a terror), came up to me near the end of my time at the school and said: ‘I don’t want you to leave.’ And then wandered off. What does that count for in the great scheme of things? I’m not sure: but I’d like to hope it was worth something

Evaluation

Focusing on persuading students history matters meant I spent a lot of time thinking about the purposes of my lessons and considering how best to communicate this with my students. It led me to work in a more democratic way – a managed democracy, certainly, but one in which I gave my students genuine choices and was open with them about the rationale for what was on offer and the decisions I made. The more I did this and they responded, the more I was happy to be open and honest about the problems I was facing or things I didn’t know how to do. Clarity about purposes and honesty with them improved our relationships and meant that they better understood why they were doing what they were doing and so chose to buy into it.

My plans evolved as I worked. Although there were some things I had in mind early on (like visiting a primary school) much was unplanned; there were many points at which I wasn’t clear about much beyond the next step. I acted by instinct and – for the most part – it worked – but it was pretty terrifying at times and it’s not something I would recommend lightly.

Were I doing this again, I would insist on a higher standard of work and behaviour from the start. At the time I though I was doing pretty well – I judge myself now against a school with higher non-negotiables. The time to chase every child and every piece of work myself, together with another four Key Stage 3 classes, Year 10s, Year 11s, A-level coursework and the UCAS system simply wasn’t there (especially in a system which demanded assessment and data entry six times a year). I’m in awe of those who can honestly do this and maintain their sanity. I did throw my teddies out of the pram on one occasion and make the whole class rewrite an essay – and I got some very high quality writing from some students. However… I now feel that I could have done more than I did.

Did they learn enough? Possibly not. They learned a lot – but among other things I dropped some topics to provide enough time to do others well. I told myself then that I’d done more of a favour by getting them to study history so they would keep learning. I look at these things differently now and appreciate this better – more knowledge and understanding provides the secure basis for later success. Could I have pushed them further? When I visited the school again in October, many of them were struggling with their GCSEs. Why?

I had a massive amount of latitude. I was in an ‘Outstanding’ school, subject to only one lesson observation a year. I don’t think anyone really knew what I was doing… How acceptable is this? Had I had to follow the curriculum to the letter, I’m sure I would have been faced by some fairly mutinous students all year. And yet most schools do not provide this space for teachers. What would I recommend to teachers who don’t have this latitude? I think spending five minutes at the end of a lesson to discuss why the lesson just studied matters – how it links with our lives or the present day. But there’s a broader question here: if teachers (and schools) don’t have freedom to innovate and experiment, how can they meet the needs of their students? Equally, once they do have that freedom, what’s to keep their choices at least somewhere related to their straight and narrow.

Intervention in Year 9 is too late! This worked, but it’s not the best way to do it. If you are trying to convert students from a negative impression of the subject, it’s hard work doing this in a year. It can be done, but this is not the most productive approach. We need to work harder in Year 7 to ensure students love and appreciate history.

Nor does an approach like this substitute for effective behaviour management, on the part of the school and the teacher. One of my struggles was getting all my students to try as hard as I’d have liked them to do on their written work – or indeed, any task needing sustained application. Equally, classroom management alone is sufficient neither to ensure students’ best efforts nor to ensure students pursue your subject with genuine interest.

Much of what I did doesn’t diverge far from what we might teach anyway. Everything I taught was on the syllabus, except the London Riots (and even that was just a tweak of the syllabus: we studied the crisis in Syria this year in Year 8, of which more anon). What this approach does is reverses the agenda, or the direction I’m pursuing – beginning with students and moving to history, rather than treating history as thing to press onto students. The best case is having seen an example like the one above, students recognise the links between what matters to them and what they learn and then formulate them independently: one of my students in Year 7 did this spontaneously last week for almost the first time ever.

Conclusion – would I do it again?

Curriculum time is precious at Key Stage 3, but investment in these inputs can make all the difference between desultory compliance on the part of pupils, and wholehearted and enthusiastic commitment to wanting to do history, to do well in it, and to do it for as long as possible.

(Ibid., p. 48)

Aspects of what I’ve described above still make me uncomfortable. There are many things which I would change: for a start, I would demand far better written work from the beginning. I would be less sanguine about playing fast and loose with the curriculum. One particular thought-experiment I haven’t considered enough if how I would react as a head of department if one of my teachers did this without talking to me about it first (as I did).

On the other hand, I believe the fundamental approach is sound. I went from having four students who had something positive to say about history at the start of the year, to having seventeen choose to keep studying the subject. Moreover, irrespective of their choices, students experienced things of enduring value: persuasive essay writing, identifying and analysing propaganda and teaching primary school students. This experience has shaped a unit themed around historical relevance with which I begin the Year 7 curriculum (and similar units for Years 8 and 9). With each class, the approach I take is different (I may come back to this in future) but with all of the, the result should look something like this – three photos of Year 7 work from last half term:

Notes

* It’s not entirely clear from Harris and Haydn’s published report how bad the picture is. 70% of their respondents said history was useful. Of 1,500 comments about its usefulness, 658 were tautological ‘It’s on the curriculum because people need to learn it.’ Over 250 appeared to offer statements which demonstrated an understanding of the rationale as expressed by the National Curriculum. Over 200 responses related to employment – although many (around 50) were phrased as though history would only be useful if you wished to be a history teacher/work in a museum. The best guess possible from the article is that around 400 students, from a sample of 1,500 who commented, were able to articulate ‘valid’ purposes of school history.

* More tricksy psychology: asking people to persuade others of something makes them more likely to believe it themselves. I knew by this stage I wasn’t going to be at the school next year, but I thought it would be a worthwhile exercise for my students.

Further reading

There doesn’t seem to be much written about this – please point me towards exciting things I’ve missed.

Richard Harris and Tony Haydn,‘Children’s Ideas about School History and why they matter,’ Teaching History, 132, September 2008 (paywall) although you can download the full report here.

Ben Walsh has an E-CPD unit at the History Association website on exactly this question.

Thanks for this inspiring account Harry.

There is a huge amount written about this, embracing all sorts of perspectives on what school history is for. There is also a coherent discourse among history teachers, debating the best way of doing it. A good place to start, I think, is to look at pieces such as yours, where history teachers have defined a problem and systematically sought to overcome it with new principles and practices, going to the discipline of history for these, and reflecting on their power. I am fascinated by the very diverse ways in which history teachers have done this. Five examples that are intriguing – but which go in very different directions, so don’t look for consensus here! – are the following, each of which I’ve prefaced with a very crude (distortingly crude) summary:

It’s all about showing the connection with their own diversity:

Philpott, J. and Guiney, D. (2011) ‘Exploring diversity at GCSE: making a First World War battlefields visit meaningful to all students’, Teaching History, 144.

It’s all about reading real historical scholarship rather than proxy versions of it (like you, Foster kicks off with a remark by a student that shocks and disturbs her):

Foster, R. (2011) ‘Passive receivers or constructive readers? Pupils’ experiences of an encounter with academic history’, Teaching History, 142.

It’s all about not avoiding complexity, in knowledge and in thinking:

Worth, P. (2011) Which women were executed for witchcraft? And which pupils’ cared? Low-attaining Year 8 tackle three demons: extended reading, diversity and causation’, Teaching History, 144.

It’s all about secure, thorough narrative knowledge, cemented and extended with conceptual clarity in framing the enquiry:

McDougall, H. (2013) ‘Wrestling with Stephen and Matilda: planning challenging enquiries to engage Year 7 in medieval anarchy’, Teaching HIstory, 2013.

It’s all about … Well, any attempt to classify this in a particular ‘camp’ is doomed. This one is about Britishness, narrative and content; or it’s about diversity; or, well, what is it about?

Whitburn, R. and Yemoh, S. (2012) ‘”My people struggled too”: hidden histories and heroism – a school-designed, post-14 course on multi-cultural Britain since 1945’, Teaching History, 147.

As for me, I think it’s about knowledge, gained in the form of fascinating, appalling, thrilling, humbling, disturbing, inspiring stories, and then having such security in that knowledge – micro and macro; macro gained through micro and vice versa – that they then *feel* their power in informed argument, and then learning how to argue, in *disciplined* (I mean that in about five senses!) ways. Each of the above pieces, however, has helped and humbled me in refining that vision, and raised new questions. Thanks so much for raising some more.

Thank you for adding these thoughts and references Christine – I look forward to considering a range of different ways of building on this. I think the conclusion of what you’ve written here goes to the crux of the matter – and reminds me of the ways we can thrill our students with the power of the subject.