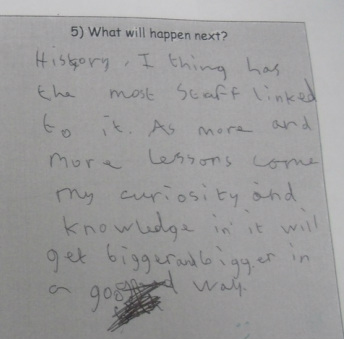

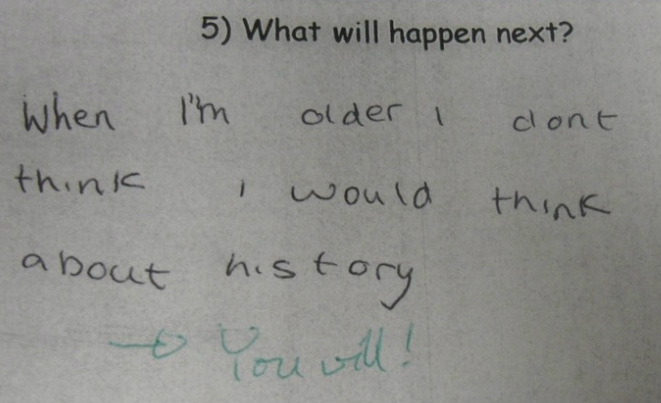

I am. This student can’t see the relevance of history. I’m working on it. Seriously though, if I can’t convince them that it matters, what is going to happen to them? Will they work hard in my lessons? Will they take an interest, study further at home? Will they choose to study history when they are no longer compelled to do so? Will they appreciate the depth behind contemporary problems or the insight the past offers? Until I can change their perceptions of the subject – probably not.

Two months ago, in a post asking ‘Why isn’t our education system working?’, Joe Kirby argued a major problem was lack of rigour. Writing, not about the “intended” National Curriculum, but “the enacted school curriculum: what actually gets taught in classrooms,” he argued :

Schemes of work in schools are admired based on how relevant and engaging they are as opposed to how rigorous and challenging they are. In principle, there is no trade-off between relevance and rigour; in practice, there is all the difference in the world…”

Michael Gove picked up and expanded upon Joe’s words; much comment attached to his discussion of the ‘Mr Men’ lesson, but he made a broader point. Quoting the passage above, he wondered whether the enacted curriculum saw “proper history teaching… being crushed under the weight of play-based pedagogy which infantilises children, teachers and our culture.”

Better men than I have taken him to task on the speech and the curriculum, notably David Cannadine, Simon Schama and Richard Evans; Russell Tarr has refuted the attack on the Mr Men lesson. I want to take issue with another pedagogical aspect of the speech: I am deeply concerned by this attack on relevance: in teaching, where it is a prerequisite of learning; in history, where it is integral to the discipline.

Relevance is a prerequisite of learning – and thus, of rigour

Daniel Willingham, quoted frequently by Michael Gove, not least in the Mr Men speech, reminds us that students need to find meaning in their learning to ensure retention. “For material to be learned (that is to end up in long-term memory), it must reside for some period in working memory – that is, students must pay attention to it (Why Don’t Students Like School, p.65).” He examines an experiment asking subjects to read a list of words- they were told either to note whether or not a word contained an A or Q, or whether it engendered pleasant or unpleasant feelings. The ‘feelings’ group remembered twice as many words (p.60). “How the student thinks of the experience completely determines what will end up in long-term memory. The obvious implication for teachers is that they must design lessons that will ensure that students are thinking about the meaning of the material p.63.” Willingham uses this to explain why teachers must consider what students will actually be focusing upon while learning (a powerpoint about the French Revolution may engender more learning about flashy animations than the storming of the Bastille). Equally, this underscores the criticality of students finding meaning in their learning.

A study conducted in American science lessons reinforces this message and identifies the impact of perceived relevance on motivation and subject choice. In a randomised controlled trial, Hulleman and Harackiewicz demonstrated that encouraging students to make connections between their lives and what they were learning in science “Increased interest in science and course grades for students with low success expectations.” They particularly underlined the importance of this for disadvantaged students who “May not perceive, or may have a harder time perceiving, relevance and value in their schoolwork.” They also noted that “Interest is a more powerful predictor of future choices than prior achievement or demographic variables,” something particularly important for history teachers.

If students believe they are being presented with material which is irrelevant to them and their lives, they are unlikely to take an interest in it and so to retain it. If students feel something about what they learn (the despair of a slave, the excitement of the start of the Renaissance, the momentum of the Nazi takeover of power), they are far more likely to remember it. And this is particularly appropriate for students who may not immediately perceive the meaning of the material they are being offered.

What this looks like in practice:

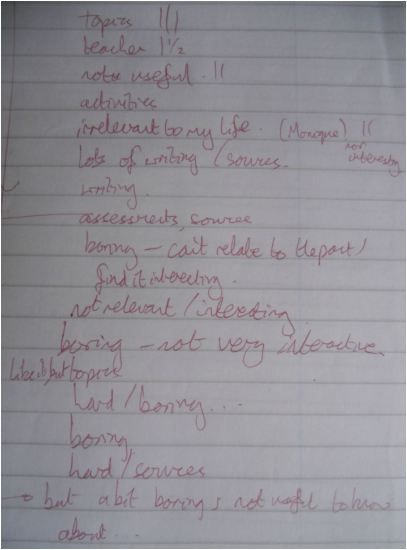

This picture is my list of reasons given by twenty Year 9 students (of 24) for not linking history, when I asked them in the first lesson of the year.

The underlying sentiment is clear: the subject lacks meaning or connection to their lives. This was a challenging, wonderful group of individuals with a huge amount to offer and they didn’t see any point in learning history.

I spent an entire term ‘off-piste,’ covering the scheme of work only incidentally, examining historical and philosophical dilemmas which exemplified the importance of history. We looked at problems like what caused the London riots as historians; not only did this lead to fascinating discussion, it inspired Zelal to visit a police station to ask for arrest statistics (I recount this adventurous term here).

Three months later, the relevance and importance of history were entrenched in their minds – then I aimed for rigour. The first thing I got them to do was to write and then rewrite essays on the causes of the London riots. Throughout the rest of the year, I kept underscoring the relevance of what we were learning, but also pushed them as hard as I could. Students worked exceptionally hard and ended up with far higher levels and far greater engagement in history. Nineteen students picked history for GCSE at the end of the year, a rate three times the school average.

Now, just reverse this order – or simply assume that all they needed was more rigour. What they needed was to love the subject and to be pushed to be brilliant at it. I had tried rigour alone the year before; it worked for some individuals, but for the class as a whole, it failed to motivate or engage, behaviour and choices at GCSE reflected that.

Motivation matters. Meaning matters. Relevance matters. I would love to hear from anyone teaching in a deprived or just a non-selective school, how they bring out the best in students without showing them the relevance and importance of what they are learning. There are many ways to do this – one of the great challenges is taking an apparently arcane topic and showing its relevance. But I challenge anyone to dispense with this and succeed in motivating and inspiring their students.

When we learn history, we seek relevance

In studying history we learn fascinating stories and imagine other times; equally, we understand our world better. If I didn’t see this relevance, I cannot imagine myself so enthralled by the subject.

This doesn’t mean that we should only seek to teach ‘relevant’ topics. Rather, we should take ancient, ‘difficult’, unfamiliar topics and identify what makes them relevant.

To offer one example, Jeremy McInerney notes in his course on Ancient Athens:

The Greeks established democracy, valued the rule of law, and articulated definitions of freedom and virtue. At the same time they owned slaves, denied women a public voice, and asserted their racial superiority… They were a complex, complicated civilization, and we are their descendants… By engaging with the Greeks, we may come to understand our own world more fully.”

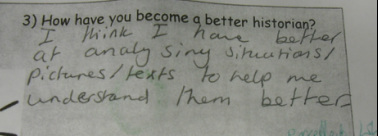

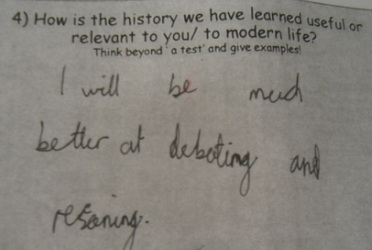

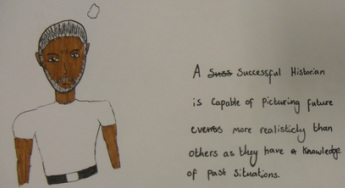

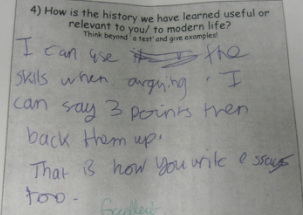

*Almost all the remaining photos in this blog are student responses to a question I include on their half-termly reflection sheets, which is adapted from the work of Hulleman and Harackiewicz cited earlier: How is the history we have learned useful or relevant to you/to modern life?

Not just Athens though – we can learn more about how multicultural societies rise and fall from Convivencia Spain, trace the fear of the ‘undeserving poor’ from Elizabethan Poor Laws, consider the importance of individual liberty through the Putney Debates. Every aspect of history has relevance to some aspect of our lives today, it is intrinsic to the subject. Once you highlight this way of seeing, students will do the same: two years ago, in her first lesson on the Cold War, Penelope spontaneously likened its proxy conflicts to the Byzantine Empire’s system of client states (she was someone who did choose History GCSE).

Michael Gove believes the past is relevant to us, too. In one speech, he argued that: “All of us, I am sure, were inspired by a teacher or teachers who kindled a love of knowledge, a restless curiosity, and a passion for our subject when we were young.”

Michael Gove believes the past is relevant to us, too. In one speech, he argued that: “All of us, I am sure, were inspired by a teacher or teachers who kindled a love of knowledge, a restless curiosity, and a passion for our subject when we were young.”

“Shakespeare’s dramas, Milton’s verse, Newton’s breakthroughs, Curie’s discoveries, Leibniz’s genius, Turing’s innovation, Beethoven’s music, Turner’s painting, Macmillan’s choreography, Zuckerberg’s brilliance. And all of us, I believe, want to excite the next generation – as we were excited – by the adventure of learning.”

“Shakespeare’s dramas, Milton’s verse, Newton’s breakthroughs, Curie’s discoveries, Leibniz’s genius, Turing’s innovation, Beethoven’s music, Turner’s painting, Macmillan’s choreography, Zuckerberg’s brilliance. And all of us, I believe, want to excite the next generation – as we were excited – by the adventure of learning.”

He wants the history curriculum to affect young people too; his call for “Space for study of the heroes and heroines whose example is truly inspirational,” implies, presumably that they see these heroes as offering a relevant example to their lives. Although he and I might choose different heroes and heroines (see, for example, Schama on Clive of India), we agree on this at least.

He wants the history curriculum to affect young people too; his call for “Space for study of the heroes and heroines whose example is truly inspirational,” implies, presumably that they see these heroes as offering a relevant example to their lives. Although he and I might choose different heroes and heroines (see, for example, Schama on Clive of India), we agree on this at least.

If Mr Gove believes, as it appears he does, history should be relevant to students, attacking teachers who show this relevance seems counter-productive.

When we learn history we acquire habits of mind which serve us well elsewhere

Another huge pleasure offered by history is the chance to get involved with a knotty problem – what actually happened? When our witnesses disagree or our interpreters clash, we are forced to investigate problems thoughtfully, reading between the lines, seeking every source possible, sometimes falling back on our intuition – and presenting our conclusions convincingly.

Another huge pleasure offered by history is the chance to get involved with a knotty problem – what actually happened? When our witnesses disagree or our interpreters clash, we are forced to investigate problems thoughtfully, reading between the lines, seeking every source possible, sometimes falling back on our intuition – and presenting our conclusions convincingly.

I am tip-toeing around the word ‘skills’ here. Daniel Willingham has offered strong evidence that ‘skills,’ as such, do not transfer easily between domains. (Or rather, that novices and experts approach problems differently, so teaching students the practice of experts is not always helpful).

I am tip-toeing around the word ‘skills’ here. Daniel Willingham has offered strong evidence that ‘skills,’ as such, do not transfer easily between domains. (Or rather, that novices and experts approach problems differently, so teaching students the practice of experts is not always helpful).

So let me use another term – ‘habits of mind.’ One of the first things my students learn is that any statement must be backed up by evidence. This habit, of justifying your thoughts, will serve students well in any context. With time and practice, broader structures for arguments can transfer too.

So let me use another term – ‘habits of mind.’ One of the first things my students learn is that any statement must be backed up by evidence. This habit, of justifying your thoughts, will serve students well in any context. With time and practice, broader structures for arguments can transfer too.

Willingham, ever reasonable, also noted that activities appropriate for experts may be justified for other reasons- he particularly notes motivation (pp.142-3) – he just cautions teachers to be mindful that the result is likely to be motivation, rather than deep learning of a topic.

When Ananama said to me a year ago – “I want to be a journalist – I don’t see how history is relevant to that…” I asked her what journalists do. “They research things, find out what happened, then write articles.” We quickly agreed that this was exactly what a historian does.

When Ananama said to me a year ago – “I want to be a journalist – I don’t see how history is relevant to that…” I asked her what journalists do. “They research things, find out what happened, then write articles.” We quickly agreed that this was exactly what a historian does.

She was in Year 8 – a long way from mastery. However, with that boost in motivation, I can imagine her continued study of the subject and additional effort towards it. I could even suggest that this might have the effect of nudging her to pursue the subject with sufficient evidence and hard work to reach mastery. This would certainly make her a good candidate for journalism.

She was in Year 8 – a long way from mastery. However, with that boost in motivation, I can imagine her continued study of the subject and additional effort towards it. I could even suggest that this might have the effect of nudging her to pursue the subject with sufficient evidence and hard work to reach mastery. This would certainly make her a good candidate for journalism.

In sum, if skills are to transfer (and Willingham doesn’t say this is a bad idea, he says it’s much harder than we imagine), if students are to be motivated, then we could and should be noting the relevance of history.

Conclusion

Teachers have a hard job persuading students that anything they are teaching them matters, doubly so in deprived communities or with students who may not share teachers’ views as to the value of education itself.

Teachers have a hard job persuading students that anything they are teaching them matters, doubly so in deprived communities or with students who may not share teachers’ views as to the value of education itself.

If teachers need to highlight the relevance of the subject, the topic or the habits of mind this builds, then they need space and support to do so.

If there is another solution to engaging students, getting them learning, I’d love to hear it – but it is not rigour alone, nor discipline alone. These are important. But they force compliance, not a love of learning – they are temporary student. In history’s case, a solution relying on these approaches alone is likely to lose us the student at 14. In English, there is, of course, compulsion to continue studying – but we risk a deeper disengagement with Shakespeare, or reading, let’s say.

I have been inspired by a couple of people promoting deeply rigorous approaches to their classes in the last week. Learning about Jo Facer teaching her Year 7s Chaucer, her Year 9s The Odyssey, or Joe Kirby setting out to ensure his students really understand Dickens’ context made me genuinely envious of their students. I asked Jo how she enthused her students with Chaucer, part of her answer read: “With year 7, I don’t think I would go down the “English canon, important, blah” route. They just aren’t interested. Like the Ofsted English report says, try to enthuse year 7 about GCSEs and they just don’t get it.”

We are dealing with children – wonderful, articulate, brilliant children, but children nonetheless. Let’s not condemn teachers attempting to make what they are learning relevant to them. Let’s be critical about the approach we take, let’s be wary of approaches which inject relevance at the expense of learning or rigour. But let us not pretend removing the relevance and relying on rigour alone is a solution.

Let us, instead, engage our students in that rigour and work with them to find the meaning in the curriculum and the desire to excel – rather than pretending we can impose excellence upon them.

This blog post has grown and been split at least three ways; next week I will talk about what the history curriculum looks like – and what it might look like.

Comments

I really enjoyed reading this Harry. You make an important point about the relationship between rigorous lessons and students’ motivation to learn. You delve into the murkiness of the myth that a well planned lesson will ward off any behavioural problems (taken quite a wide definition of behaviour here). We can plan the most amazing, academically rigorous lessons that are good history, but students may still not want to learn. They bring a lot with them to the classroom, such as their perceptions of history and its value. Planning to work on this is really useful, and it appears to be paying dividends for you.

I found it myself working with a difficult year nine class at my last school. I had taken ideas from all over the place on learning the Holocaust and I believe I planned some very good lessons. The problem was, the students were simply not motivated. This lethargy degenerated to a point where one of my students raised the question “why should we bother?” This exposed the terrible flaw in my planning, I had simply assumed that their would be an intrinsic motivation to follow the Holocaust. Not so for many of our students from the demographics you touch upon.

My solution was actually to throw this question to the floor and we spent the best part of a 100 minute lesson debating and discussing this point. Students really got into it, and I got quite a good insight into what mattered to my students in life, and from history. For example, the place of slavery on the curriculum and the value of studying it was thrown up by the students and discussed at length – before we probed the relative horrors of the Holocaust and the Slave Trade (weak students then took this in the excellent tangent I would want; why would we want to compare two horrors? Is that right?)

An understanding of the value of learning something is vital to our students participating in rigorous learning. I’d suggest that this was still the case for selective/higher-ability students whose motivation is more task rather than learning orientated.

I’d be interested to see the ways in which you try to motivate your students to learn history. Here you spend a lot of time on “relevance”, are there other motivating factors?

I thoroughly look forward to your views on the NC in a future post. I’m also already intrigued by Zelal’s story and look forward to seeing this appear in your blog in the future!

Reply

Thank you for these comments, which really add to what’s in the post. Coming across this issue with the Holocaust is a really good example of why it matters… your solution sounds admirable.

The point about task-orientation is certainly well-made – higher attaining students may well have very different barriers to valuing their learning for its own sake, but those barriers are equally important.

In terms of motivational factors, a couple of years ago I saw a list of ten ‘motivational drivers’ – which included choice, interest, success, autonomy, fun… the point made (which is certainly true for me) was that as teachers we often rely on interest and barely touch on some of the other drivers. I’ll dig it out – but I think we need to try to balance all of them.

Thanks for the kind words. When are you going to start your own blog?

Reply

Thanks Harry!

I occasionally pass comment on my blog here http://urbanhistorypgce.blogspot.co.uk/2013/06/a-placement-at-british-museum.html however its not very good. The name is a bit out of date too, what with the PGCE finishing. Now that a less hectic schedule is nearly upon me I’m thinking about a relaunch and making it a bit more professional, along similar lines to yourself with extremely interesting posts on history pedagogy.

As always a very intelligent blog. I’d read your stuff if it was about toilet paper, because I find I can always find something I can relate to. Important phrase for me, relate to. MUCH more important than relevant. It is very difficult to make a piece of learning relevant – I might not find any relevance in the life of (insert name of historical figure) at all. But I may find I can relate to the challenge of the learning, or to the superb use of language, or to the art of the picture you show me, or the logic of the science in the document investigation. Get what I mean. Relate to before relevant to. I think that works.

Keep writing and blogging, please.

Reply

I was reading Malcolm Gladwell today on how he felt at one stage it would be interesting to write about shampoo. Perhaps I’ll come on to toilet paper in due course.

Thank you for your thoughts on this… relate to is perhaps a good way of putting it – particularly given the broader terms for deriving interest you have used here. I like the idea that a student might not find the relevance of the topic engaging, but might relate to some other aspect of the delivery.

Reply

It is true that History suffers more than other subjects from students questioning its relevance. You have devised some lessons that have persuaded the students of the subject’s worth and that is great. However, I question your assumption that the students begin to enjoy history when they see its relevance. I asked my 10 year old why she liked History at school and she said she liked the stories and knowing they happened to real people. When I suggested the idea that history was interesting when she could see the relevance to her life she looked plain bemused. OK, she is unjaded by secondary schooling, the daughter of a history teacher and goes to a ‘nice school’ but are you suggesting that the children you describe, from poorer backgrounds have less appreciation for a good story? Was Braveheart boring because it wasn’t relevant? Are Horrible Histories a right bore because the sketches are not relevant? You invested a lot of energy into making an interesting unit of study on the relevance of History but the story itself is also interesting. Could you have made them find History enjoyable by investing all that energy in socking them a great yarn? I am concerned that letting relevance guide your curriculum choices puts the cart before the horse. I have no problem with telling children why History is important and taking opportunities to emphasise this whenever. I also try hard to tell the story of History in a way that helps the children build on their existing understanding of the world and thus I try to draw paralells with modern situations. I would also sell the importance of my subject to secure uptake at GCSE and A Level. However, students tend to enjoy history because it is innately interesting

Reply

I completely agree about the innate interest of history… it’s something that has always drawn me to it.

I don’t tell stories as such, as some history teachers do very successfully, simply because I don’t believe I’m a particularly good raconteur – I’m not the kind of person who tells stories socially, for example – and I don’t think I have the capacity to hold the attention of a class while I unfold a narrative. I’ve played around with this but never really taken to it.

I do use stories as teaching tools very often though – to bring history alive, demonstrate the impact of events on a human scale, provide structure to a lesson (and for their memorable nature, another thing highlighted by Daniel Willingham). I’m a firm follower of Stalin here: one death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic. So I try to focus students on the lives of individuals as exemplary of great changes in history.

My focus on relevance has derived from my observation that the single most frequent complaint/demotivator in the students I have taught has been that history is a) boring or b) irrelevant – I have tailored the solution to fit the problem as I have found it. I wouldn’t claim that this is the whole solution to motivating students in history – just that it works for me.

The only other point I’d make is that relevance may motivate some of the processes of ‘academic’ history (like analysis, source evaluation) in a way narrative does not.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts – perhaps it’s time for me to go back to narrative and play around with it some more.

Reply

Please excuse typos. I can (sort of) spell and punctuate really.

Reply

Not something I would deny for a moment! Thank you to the link, that’s an interesting article – I think this approach fits into all four of the different ‘purposes of history’ given – although a teacher could prioritise one or more if they chose.

There are so many more aspects of the curriculum which the article raises really well – perhaps foolhardy given the depth of thought others have given to the history curriculum, but I’m going to comment on some of them later this week.

Reply

For some inspiration on teaching about the relevance of history, see Michael L. Umphrey’s book The Power of Community-Centered Education: Teaching as a Craft of Place.

A very short introduction to the book from my perspective as a writing teacher is at http://ilnk.me/1482c on the YouCanTeachWriting blog.

Thank you for putting this case so thoughtfully. I found it fascinating. I’ve also really enjoyed reading your students’ reflections.

Thank you Michelle.