Good to great comes about by a cumulative process – step by step, action by action, decision by decision, turn by turn of the flywheel – that adds up to sustained and spectacular results.”

(Jim Collins, Good to Great, p.165)

I concluded my last post, on Good to Great, by questioning whether schools without a ‘hedgehog concept’, a single focus, could pursue this flywheel model of improvement. In this post I’d like to consider the role of ‘flywheel’ improvement in my own classroom.

The merits of continual refinement can be inferred by the contrasting experience of the companies Collins studied which failed to improve:

“They sought the single defining action, the grand progam, the one killer innovation, the miracle moment that would allow them to skip the arduous buildup stage and jump right to breakthrough. They would push the flywheel in one direction, then stop, change course, and throw it in in a new direction – and then they would stop, change course, and throw it into yet another direction (p.178).” I think this cycle, which Collins called a ‘Doom Loop,’ describes teaching and learning initiatives in many schools and classrooms, particularly those orbiting the ‘planet Ofsted, rather than the planet Pupil,’ (as Tessa Matthews so elegantly put it).

How does this link with classroom teaching?

Harry – please keep sharing the iterative processes of things like this. It’s fascinating to be able to see the consequences of what you are doing, and how you are reinforcing. Often this part of the thinking is left hidden so teachers believe that a one-hit “perfect” lesson is enough. What you’re doing here shows how students have many different reactions to materials they are shown at school. Teachers then need to consider what they’re thinking, reformulate, rediscuss and keep them thinking at if we want to have a long-term impact.

Teachers are like magpies. They love picking up shiny little ideas from one classroom; taking it back to their classroom; trying it once, and then moving on to the next shiny idea.” (Dylan Wiliam, via Old Andrew)

In terms of ‘continuous’ professional development, the consequences are dire: they disorient students and teachers alike, preventing either from obtaining the best from the techniques available, let alone mastering them.

Having been blogging for six months, I want to revisit and review some of the improvements I have attempted. This feels slightly solipsistic and certainly one purpose of this post has been to stimulate my own reflection. However, I hope it will also act as a chance to share the iterative process I’m trying to pursue, and be an opportunity to be honest about the limitations of these improvements, avoiding the impression of unchecked progress which the ‘happily ever after’ endings of some posts might imply. I’ve tried drawing some tentative conclusions about how I might continue to improve my teaching in the conclusion.(I’ve provided links to the original posts, in case that helps make sense of them).

Increasing wait time

My first blog post was on increasing wait time: waiting three seconds after asking a question to nominate a student to answer it, waiting three seconds from their response before responding.

Then…

I found the experience strange (it’s an unnaturally long wait) but useful, noting that it led to deeper contributions from students, particularly those who were unaccustomed to making sustained points; overall, it led to more considered, thoughtful discussion.

Now…

I’m still using increased wait times – but not nearly as often as before.I mentioned at the time that it took a degree of concentration to sustain this (counting in my head/with the help of the clock, the pause needed). As I have focused on other aspects of teaching, my focus upon this has faded. Sometimes I wait, but not long enough, sometimes I forget entirely (and then kick myself).

Equally, I am trying to take a more nuanced approach (this is, after all, supposed to be a sign of good teaching – knowing when to apply rules and when not). Sometimes, I want a swifter pace of debate or the chance to make or hear a number of brief points or ask a lower order question. At other times, a slower pace is helpful.I also noted at the time that some students didn’t know when to stop. I think, through lasting pressure on this handful of individuals, from my colleagues and me, they are learning succinctness.

Conclusion…

The literature noted that even in research projects specifically targeting wait time, a significant proportion of teachers did not sustain an increase. I need to return to this technique and concentrate upon it for longer if I am to incorporate it into my teaching.

Hinge questions

I was dazzled by hinge questions, enjoyed experimenting with them and introducing them to my students and learned a lot about the misconceptions they were making and (often) how little they were really understanding from my lessons. I struggled with integrating them into my teaching as I wrestled with these misunderstandings and sought ways to correct them easily.

Now…

I still really like them. I am probably averaging one hinge question every two or three lessons. They are sufficiently routine that, when wondering aloud whether to take the time for a brief review of a previous topic, one student suggested: “Couldn’t you give us a hinge question?” Fortunately, I had one up my sleeve. This student had questioned their usefulness when I introduced them, so this represents an interesting shift in his understanding.

They have also catalysed a broader improvement in my practice, as I use similar techniques to conduct minute-by-minute checks on student understanding as issues emerge in lessons and pay closer heed to identifying and addressing misconceptions.I have also learned to adapt my approach to addressing misconceptions, acknowledging that some need significant whole-class time, while others may be best left to discuss with individuals or small groups in isolation.

Some of my colleagues have also begun using hinge questions regularly; on a recent visit to another lesson I asked a student whether he had had a hinge question in this subject recently; he replied: “Yes, we did one last Tuesday in our technical language lesson.” One colleague noted that in teaching grammar, he found them ‘really useful.’

While I can now use hinge questions confidently and frequently, I’m not spending the same amount of time thinking them through and constructing them as when I introduced them – so their quality is perhaps suffering.

On the other hand, as I have prepared to recap the entire History of Maths course, I have constructed a hinge question for every single topic; not only this, I am leading students to act as teachers and develop each others’ understanding on each question. The video below shows a tiny section of one group’s attempt to do this as they finally work out which two statements about Archimedes were false:

Something I’m happy to use and do so frequently – sufficiently appealing that my colleagues are using them too. I need to ensure I keep devoting time to improving and revisiting my questions.

‘Closing the gap’ marking

Inspired by Tom Sherrington, I looked into ways to reduce the amount of time I spent marking while ensuring students got more out of it.

Then…

This seemed a fantastic idea: I found it took a substantial amount of lesson time, but was extremely useful. There was clear evidence students better understood what a good piece of work looked like – and what they needed to do next, although I found checking all my students’ responses problematic.

Now…

– Students understand and respond to feedback more swiftly

– Students are increasingly able to identify what I am looking for, what makes a piece of work good (and then to practice this in lessons)

– I am, as I had hoped, marking more and returning work to students more quickly

– I have one class which are completing their first complete essay later than the others; the essays they have produced are, as a group, significantly better than those of the other three classes – having benefited from this technique of feedback while they were planning.

– I have adopted symbols rather than just double ticks, which students respond to

– My colleague, Caroline, shared an adaptation of this, which includes students guessing the meaning of symbols first, which appears to offer similar or better results.

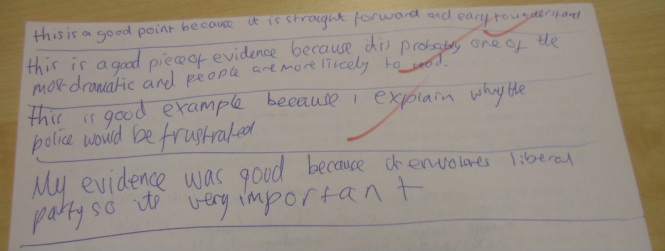

– I have dealt with the problem of checking all students’ responses by using an apparently brutal approach: ignoring almost all student questions (offering them instead a series of suggested self-help and peer strategies) and using the time to attend to each student one at a time, reading their written responses, ticking if I am happy and moving on, returning repeatedly if I am not and offering hints and support until students write a suitable response.Here is a recent example. It demonstrates that a) This student has not only understood the structure of a paragraph, but has begun to identify how to make that paragraph a beautiful piece of writing (for example, by choosing the ‘dramatic’ bits of evidence, and b) I had time to check it!

Conclusion…

This has been hugely helpful, saved an enormous amount of time, improved students’ peer and self assessment and got me marking more.

Knowledge and skills

Then…

I enjoyed the book and it prompted me to reflect on issues such as working memory. I argued his arguments had been exaggerated by those who promote knowledge ‘above’ skills and that they were useful but not novel.

Now…

The importance of the book and its ideas has grown for me. Inspired by the book, and the frequent evocation of its ideas by blogs such as Tessa Matthews’, I am spending more time considering working memory and the role of knowledge in supporting analysis and understanding. While the other topics here I set out to address intentionally, this was almost accidental – a product of the continuing reflections engendered by the book. I am still not just ‘teaching facts;’ rather I am devoting more time to repetition, to help students build up familiarity with individual elements of a topic in the process of moving towards analysis, ensuring a background understanding along with skill development. For example, in a recent unit on Africa in Geography, I allocated time to build up a familiarity with the continent’s geography (locations of places, physical features), so that we were able to look at more complicated issues such as the effect of climate change on people’s lives without students trying to work out North from South and savannah from rainforest.

Conclusion…

This has really helped me to ensure students’ understanding develops well and is sustained. I’m not ditching the importance of a skilled application of knowledge, what I’m doing is thinking more clearly about how secure the bottom step of Bloom’s taxonomy is and how to improve it as a prerequisite to moving up to analysis. (Increasingly, I am taken with Sam Freedman’s explanation that skills are a form of knowledge).

Evaluation

I think that, taken together, this means I should:

1) Focus on one improvement at a time. In January, I tried two at once; while I recognised the power of both, applying them simultaneously, while maintaining everything else, pushed my teaching to the limit. To mindfully and genuinely improve, I think I can only introduce one novel technique at a time.

2) Perhaps the moment an improvement is starting to bear fruit is the point at which I should redouble my focus upon it. This is something which only occurred to me as I wrote this post and reflected upon the extent to which I had let some of these techniques slip. I reached a half term, evaluated and moved on. Perhaps this was an error. The point at which I begin to see positive results is probably the point to really get to work on refining the technique – particularly if I am to find a permanent place for it in my teaching.

3) Yet this must be balanced with a desire for novelty on my part, and that of my students. I don’t have a problem with this – I want to try new things and students can get tired of the repetition and experimentation required for me to master a new technique. I intend to maintain a rule of introducing one new technique/idea/improvement/focus each term, but for two foci next year to be hinge questions and wait time, with a view to perfecting them.

4) My aim is to automate these complicated processes. I think about the things which have become second nature to me – like getting twenty-five students in, sitting down and learning in under a minute, or getting all the resources into the right place as quickly as possible, or (usually) refocussing an errant child. When I entered teaching, these took all my concentration; now I can have a one-to-one while scanning the rest of the classroom simultaneously: practice makes a habit of them, incorporates them in my repertoire, When I began using coloured cups/cards with students I had to plan it, introduce it, trial it, teach students what I want. I don’t really have to think about how I use them now. I hope, in a year or two, that sufficient wait time and good use of hinge questions will be in a similar position – and then it will be time to move on.

In sum:

We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.”

Aristotle

It may be cliched, but, as Caldies T&L tweeted a few days ago, it’s possibly something worth repeating to oneself once a week forever.

Logical further reading includes:

- Joe Kirby’s recent post on CPD, the importance of evaluating CPD and links with Doug Lemov’s work on practising teaching skills.

- Zoe Elder’s work on Marginal Learning Gains, which is this idea of constant refinement writ large.

I have taken an AfL approach to highlighting the key teaching strategies I wish to master. Recently, two great teacher bloggers have identified different ‘holy trinities’ of teaching.

- Speaking of Maths, Kris Boulton has named: understanding, thinking and questioning.

- Of English, Alex Quigley, has highlighted questioning, feedback and explanation.

I don’t know if I agree with their choices, but if you’re looking for single things to focus on improving, they must make a great starting point.

Update:

Building on the interest in this post and my reflections upon it, I have written up my development priorities for 2013-14 here.

[Originally posted 9th June, 2013]

Comments

Just super. Love the processes you are using and the way you are refining them. Thanks

Reply

Reading through this post I felt myself inspired again by the ways in which teachers seek continuous incremental improvement. Thank you so much!

Seriously important piece. No quick fixes. Doing a few things really well. So important colleagues take on board that it’s not being a magpie, or looking for ghastly cheap tricks for teaching. Spot on, keep going.

This is excellent, really excellent. Well done, thank you and keep em coming.

Good piece, Harry. I note that much of your work described here focuses on trying or improving techniques and then attempting to work through and see impact on any part of students’ learning. I would suggest that this may be the wrong way around. You can begin by identifying the gaps between where students are and where you want them to be and *then* decide which technique you can implement/improve. This allows you to clearly evaluate impact (has the gap closed), it ensures you are always focused on student need and not just your own desire to innovate, while also ensuring you develop and refine the technique in a way that responds to student need and not just fidelity with some described approach elsewhere.

This sort of process of teacher enquiry has been reported to be more successful with its basis in student learning rather than teacher practice, and ideas such as Lesson Study benefit from this approach.

Interesting point David, thank you for the comment. As I tried to explain in my talk at Pedagoo London this year, I agree with you that identifying students’ needs comes first, while having some degree of appreciation of how you might meet those needs is also a prerequisite to change.

One example was my attempt to improve my use of learning objectives – where I first evaluated the effectiveness of my existing practice and considered possible approaches – and then put them into practice.

That said (and hopefully without contradicting myself), one of the things I very much like about formative assessment, on the other hand, is that it does provide us with a clear menu of techniques to master… and I think that for all I’ve said above about seeking out the gaps, it is helpful to start with this idea of what the key features of learning are first, as something to keep in mind when looking at students’ current performance.